21 Aug The Juracan Juracan Case

This article will exclusively address the interpretation aspect of the proceedings, omitting other case background and charges, which are readily available online. The defendant, Oscar Juracan Juracan, faces 1st-degree criminal charges before the Hudson County Superior Court in New Jersey and is a speaker of Kaqchikel, a Mayan language. A jury trial in this matter would require relay interpreting between English, Spanish, and Kaqchikel, as no Kaqchikel-English interpreter was found. All pre-trial proceedings were conducted using remote relay interpreting. Despite the Kaqchikel interpreter’s expressed concerns during trial-planning discussions, the trial court ruled that the jury trial should proceed with remote interpretation. The defense appealed, and after the appellate court upheld the decision, the matter went before the New Jersey Supreme Court, where oral arguments were presented on June 1st. The ACLU of New Jersey represented Amici Curiae NAJIT and the ATA, and Latino Justice PRLDEF, a civil- and human-rights organization, also acted as amicus curiae.

This article will exclusively address the interpretation aspect of the proceedings, omitting other case background and charges, which are readily available online. The defendant, Oscar Juracan Juracan, faces 1st-degree criminal charges before the Hudson County Superior Court in New Jersey and is a speaker of Kaqchikel, a Mayan language. A jury trial in this matter would require relay interpreting between English, Spanish, and Kaqchikel, as no Kaqchikel-English interpreter was found. All pre-trial proceedings were conducted using remote relay interpreting. Despite the Kaqchikel interpreter’s expressed concerns during trial-planning discussions, the trial court ruled that the jury trial should proceed with remote interpretation. The defense appealed, and after the appellate court upheld the decision, the matter went before the New Jersey Supreme Court, where oral arguments were presented on June 1st. The ACLU of New Jersey represented Amici Curiae NAJIT and the ATA, and Latino Justice PRLDEF, a civil- and human-rights organization, also acted as amicus curiae.

On August 15, 2023, the Supreme Court issued a ruling remanding the matter to the trial court for reconsideration of the appropriateness of VRI. Further discussion of the ruling will follow after the summary of the arguments.

Defense counsel advocated for a categorical rule against remote interpreting in criminal trials unless an interpreter’s physical presence is impossible, contending that there is no way to protect the defendant from the frustrations and adverse impressions of the jury caused by the inevitable interruptions. Challenges exist with relay interpreting, whether in person or remotely, but remote interpreting amplifies these issues and would lead to violations of the fundamental notions of fairness and due process. Defense counsel considers that no safeguards could adequately ensure fundamental fairness in a criminal trial with remote interpreting. Some problems inherent to remote interpreting are simply “not fixable” and pose too much risk in a criminal trial. The fundamental distinction between pre-trial proceedings and a trial is the presence of the jury.

Key points from the defense brief:

- Inherent practical difficulties with remote interpretation make it unsuitable for a criminal trial;

- Proceeding remotely at trial would prejudice the defendant;

- To avoid constitutional issues, the Language Access Plan should be interpreted to exclude remote interpretation in criminal trials.

One of the issues of note cited was the defendant’s need to be able to immediately react and have a private conversation with counsel, which, in a remote setup, would be “enormously disruptive” to the proceedings, requiring a virtual breakout room and possibly the attorney physically leaving the courtroom. In this matter, the Kaqchikel interpreter also stated his availability and willingness to come in person as well as his “profound discomfort” with carrying on remotely for a jury trial.

As to cost considerations, the defense stated that, when constitutional rights and possible decades of incarceration are at stake, subjecting the matter to a cost analysis would not be appropriate. As a practical matter, the defense counsel pointed out that the interpreter’s hourly fee constitutes the bulk of the cost, so the only savings would be travel, lodging and meals. In the long term, this would minimize issues for appeal and avoid other costs in terms of time and money.

As to cost considerations, the defense stated that, when constitutional rights and possible decades of incarceration are at stake, subjecting the matter to a cost analysis would not be appropriate. As a practical matter, the defense counsel pointed out that the interpreter’s hourly fee constitutes the bulk of the cost, so the only savings would be travel, lodging and meals. In the long term, this would minimize issues for appeal and avoid other costs in terms of time and money.

The defense asked the court to formalize what is already status quo in the state with a rule on a matter not previously litigated, as prior to the pandemic, there was not much consideration for holding millions of remote proceedings, nor of holding a jury trial remotely. In rebutting the cost argument, the defense mentioned that this would affect an extremely narrow subset of cases. A very low percentage of defendants proceed to trial and, within that circumstance, even fewer need interpreting, and fewer yet would be speakers of rare languages. In sum, the defense requested strong presumption in favor of in-person interpretation and urged the court to consider the interpreter’s judgment based on established codes of ethics.

Sharing the collective expertise of professional interpreters, the amicus brief presented on behalf of NAJIT and the ATA presented issues in this case that are critically important to ensuring the rights of LEP defendants in criminal trials and to their members’ ability to meet their professional standards. The ACLU, on behalf of the two organizations, argued that remote interpreting in a criminal trial would undermine the accuracy and completeness of interpretation, create serious ethical risks for interpreters, and ultimately impair the courts’ ability to recruit interpreters for criminal trials. The ACLU urged the court to defer to the interpreter’s professional judgment as to whether a proposed plan for interpreting services permits them to meet their professional standards, and also advocated for a per-se rule in favor of in-person interpreting, in line with defense counsel.

Key points from the amicus brief:

- Remote interpreting in a criminal trial is incompatible with interpreters’ professional standards, as it poses too high a risk for errors and omissions.

- Remote judiciary interpreting leads to cognitive overload and rapid fatigue.

- Limited visual access impedes interpreter performance.

- Feelings of isolation and alienation reduce interpreting quality.

- Audibility challenges, technical errors, and the need to juggle multiple communication channels impact accuracy and completeness.

- The trial court judge should have accepted the interpreter’s professional judgment.

An amicus brief, accompanied by oral arguments, was also presented on behalf of Latino Justice PRLDEF, with the stated goal of protecting the rights of a Mayan-language speaker to adequate interpretation during his criminal trial, a right already well established by New Jersey’s courts. Latino Justice firmly asserts that remote interpreting cannot suffice for a criminal trial and that LLD (languages of lesser diffusion) speakers should not be denied constitutional safeguards due to the relative scarcity of local interpreters.

Key points from the Latino Justice PRLDEF oral argument:

(1) Remote interpretation would compromise due process rights and fundamental fairness of the trial. The defendant’s meaningful participation in his defense and access to confidential discussions with counsel are essential elements of due process and fundamental fairness. The logistical intricacies of remote interpretation can jeopardize this aspect of a criminal trial.

(2) Relay interpretation poses unique challenges.

The prosecution assumed a relatively neutral stance, primarily emphasizing adherence to existing language-access plans, adding that fiscal factors should not be the focal point in making such decisions but are only one among various aspects to be weighed. Although the prosecutor did not extensively delve into the subject, acknowledging that interpretation decisions for trials are beyond the prosecution’s purview, she acknowledged the concerns raised by the other parties.

The New Jersey Supreme Court’s ruling remanded the matter to the trial court for reconsideration of whether VRI is appropriate. The Court emphasized the difference between pre-trial proceedings and criminal trials, as well as the obstacles that virtual interpreting may create for defendants to communicate with defense counsel. The Kaqchikel interpreter’s professional judgment, costs, and other factors set forth by the Court should be considered in assessing the propriety of virtual interpretation during a criminal jury trial.

The update to New Jersey’s Language Access Plan (LAP) adopted in 2022 during the pandemic now allows VRI for both “emergent and routine proceedings,” subject to judicial discretion. This defendant’s motion for in-person interpretation services during the jury trial was denied, as was the initial appeal. The New Jersey Supreme Court granted leave to appeal and set forth guidelines and factors to assist trial courts in deciding whether VRI should be used during criminal jury trials. The court found this necessary in order to guarantee protections under the Sixth Amendment and its counterpart in the New Jersey Constitution, affording criminal defendants the right to a fair trial, the right of confrontation, and the right to counsel, as well as the due-process right to be present and to fully participate during trial.

The update to New Jersey’s Language Access Plan (LAP) adopted in 2022 during the pandemic now allows VRI for both “emergent and routine proceedings,” subject to judicial discretion. This defendant’s motion for in-person interpretation services during the jury trial was denied, as was the initial appeal. The New Jersey Supreme Court granted leave to appeal and set forth guidelines and factors to assist trial courts in deciding whether VRI should be used during criminal jury trials. The court found this necessary in order to guarantee protections under the Sixth Amendment and its counterpart in the New Jersey Constitution, affording criminal defendants the right to a fair trial, the right of confrontation, and the right to counsel, as well as the due-process right to be present and to fully participate during trial.

The court ruled that there should be a presumption of in-person interpreting services for criminal jury trials. Trial courts should consider factors such as the nature, length, and complexity of the trial, the availability of an in-person interpreter, the impact of delay in obtaining an in-person interpreter, the defendant’s tentative plans to testify, the financial costs, and the interpreters’ opinions on their ability to fulfill their duties while interpreting virtually. In rare cases where VRI is used, guardrails should be put in place to ensure a fair trial.

Key points of concern and discussion during oral arguments, mainly stemming from the judges’ questions:

- to what extent, if at all, should cost be a consideration;

- “slippery slope” concerns – other defendants arguing the same about pre-trial proceedings, that they are essential and that remote interpreting cannot be used;

- should there be any extremely rare exceptions to allow for virtual interpretation in any criminal trial (the judges were wary of issuing any absolute rule);

- if such circumstances allowing for an exception exist, how could a court ensure the maximum extent of fairness.

During the oral arguments presented, a couple of issues during the discussion stood out, showing some limitations in public understanding of interpreters’ work. First, there was a brief exchange regarding team interpreters’ roles, describing one as “resting” vs. the other as “working,” highlighting a lack of information on the roles of active and passive interpreter roles in a team. One point raised that was of particular concern was a mention by one of the justices that freelance interpreters may be motivated to push for in-person trials as a way to increase their hours. This is not the case, and they are likely to spend more time on a remote relay trial troubleshooting issues than if they were in person. The defense did well in countering this argument, mentioning that taking this initial cost can help reduce much higher costs in terms of money and time spent on litigating issues on appeal.

An issue within the text of the ruling consists of references to a “court-certified Kaqchikel interpreter,” though no such certification exists, also highlighting the need to clarify terminology to those who interact with our profession.

There was a great deal of conversation regarding the issues posed, not only by VRI but also by those that are present with interpreting in general. One issue remained unresolved: that there was no second interpreter for Kaqchikel in order to ensure team interpreting. This may also be one of the challenges faced in this trial, having to ensure adequate breaks if a second interpreter cannot be found.

The judges recognized the complex nature of criminal trials as different from pre-trial hearings. They indicated the need to consider whether remote interpreting is appropriate in each particular case, taking into account in this case the complex nature of the two levels of interpreting. The fact that the interpreter himself expressed concerns and stated that he did not believe he could perform this task well, as it had never been done before, further supports this consideration.

Overall, the decision was positive, representing the next best thing to the per-se rule for which the defense and the amici curiae advocated. The court ruled in favor of a presumption against remote interpreting and set forth factors to be considered by trial courts in making determinations, including interpreter input, approval from assignment judges, and consultation with AOC. As a result, the case was remanded back to the trial judge to reconsider if VRI is appropriate.

Stay tuned for an upcoming Proteus article for a more in-depth summary of this important ruling.

Andreea Boscor is a Federally Certified Interpreter for Spanish, an approved interpreter at the Master level by the New Jersey Judiciary for Romanian and Spanish, and an ATA-certified translator for Spanish into English.

Andreea has experience in legal, medical, and conference interpreting, and prior to language work, approximately seven years of experience as a paralegal in insurance defense, commercial litigation, and securities-law settings, both in the private and public sectors. She is an active and voting member of NAJIT and ATA and has formerly served as Assistant Administrator and then newsletter editor for the ATA’s Medical Division.

Andreea resided in New Jersey since moving from Romania during her teenage years, then a new opportunity recently brought her to Southern California, where she currently resides. She holds a bachelor’s degree in Spanish with a major in translation and minors in linguistics and paralegal studies from Montclair State University, as well as a master’s in diplomacy and international relations from Seton Hall University. Andreea is passionate about lifelong education and advocacy for the interpreting and translation professions. Contact: aboscor@najit.org.

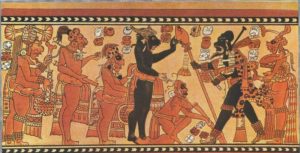

Featured photo “Bergen County Courthouse, Hackensack, New Jersey” by Ken Lund at flickr, under a CC BY-SA 2.0 license. Text-body photos: first photo “Mayan Language Map” at Wikimedia Commons, under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license; second photo “Appeals Court” by Nick Youngson at The Blue Diamond Gallery, under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license; third photo taken from “Naturalistic Aesthetic of the Mayan Civilization” by Erik Bek at The Golden Assay, under a CC BY-NC 4.0 license.

Excellent journalistic piece, Andreea. I didn’t know you could write so well! We are looking forward to reading the full article, so please keep us all posted when it comes out on Proteus, please. I will set up a reminder to tag us all. 🙂

Applause! Thank you for following this to the state Supreme Court level. These are arguments we advocate for daily as ASL interpreters and I appreciate now having something to refer to as an authority.

Andreea, excellent article! Thanks for keeping us updated on this most interesting and crucial ruling. I look forward to reading the article in Proteus. There are so many factors to consider in cases that require relay interpreting and interpreters who are in remote locations.

Wow, Andreea, thank you so much for this summary and analysis of such an important decision. It helped me understand more of what is happening right now with VRI, specifically with this case, but also more broadly, especially with the key points that you cited from the amicus brief. That part of your article is an excellent outline of things to watch out for when interpreting remotely and seeking to uphold professional standards: risk for errors and omissions, cognitive overload, fatigue, limited visual access, isolation, alienation, challenges with audio and juggling communication channels. So many possible pitfalls. I truly enjoy the act of interpreting itself and see remote interpreting as a great opportunity. I really think it’s possible to deliver excellent service remotely, but being aware of the challenges is so important!! I am glad an appeal was presented to the Supreme Court in this particular case, especially since the Kaqchikel interpreter had already expressed concerns.

Thank you, Andreea, for your well thought-out article with such granular detail. On top of all the challenges mentioned in your article, I cannot help think of yet another one:

In order to interpret using an extremely rare language such as Kaqchikel during a criminal trial (without an interpreter mate to boot). such a rare language interpreter — who may have a court assignment requiring that rare language only once a year or even with less frequency — would have to maintain legal interpreting proficiency and fluency on a consistent basis throughout the year(s), which I find straining to one’s imagination (unless the interpreter happens to have studied law in the foreign country in question and be working in the criminal law field in the United States, and actively interpreting in court using another language that is more commonly in demand.

Hello AJ: oftentimes, Mayan, Aztec, Inca, etc. language interpreters are not so well-versed in the intricacies or even the basics of the legal system themselves, and even if they are, there is the huge cultural gap between source and target language and they have to try to come up with words or phrases to define concepts that just simply do not exist in the target language culture. Case in point, the “not guilty” concept that does not exist in the Navajo culture. To the Navajo, it’s “did you do it?’. Add to that the lack of formal education of many of the defendants, who do not even receive elementary education and it becomes a really, really difficult endeavor. I can tell you a few courtroom stories where the lack of understanding of the intricate interpreting process led to errors that caused cases to be sent back on appeal. A particular case comes to mind in which yours truly even put on the record that the defendant’s primary language was NOT Spanish… A capital offense case mind you!! Here in this case the trial court should never have allowed remote interpreting, period. Good grief!

Not sure if I agree with that assessment. But we have to keep in mind that VRI has not been fully developed and it is in its infancy period. There is a fine balance between what currently works and what doesn’t when it comes to VRI (as well as in person interpreting). I have a feeling that VRI is probably best used in a case-by-case basis. Factors such as interpreters who are more familiar with VRI vs interpreters who might form opinions against VRI should be considered. Technology infrastructure and standard processes for cases will have to be available for successful use of VRI. There are other insular factors to consider but overall, I think VRI has great advantages over in person interpreting and for sure, we are finding some pitfalls which I would credit to again, lack of experience using VRI and doing VRI which is still in a development process. Sucessful use of VRI can be accomplished, I believe, even in complex and varied languages. These are my personal observations.

Given the scarcity of Kaqchikel interpreters, the interpreter is in much demand on a regular basis throughout the country. I don’t know the interpreter in question, but I worked as a remote relay interpreter many times in Federal court with a Kaqchikel interpreter who sadly passed away from COVID. He was a consummate professional and while I don’t speak Kaqchikel, his professionalism, commitment to our field and code of ethics, and Spanish skills were on par with any federal interpreter I know.

My understanding from the Spanish interpreters who have worked on this case is that they have likewise been pleased with him as a relay partner.

I am so sorry for his passing. You have honored him.

Thank you for this great analysis and your structured writing. Excellent piece! It highlights a very important subject that merits our attention as we continue discovering the advantages and challenges of remote interpreting. This case recognizes the serious disadvantage we face as remote interpreters when all the other parties are in person. The quality of our work suffers in those circumstances and it takes courage to accept it. I applaud the Kaqchikel interpreter for advocating for himself and NAJIT and ATA for their timely participation. I look forward to the Proteus article!

Great article! However, how does NAJIT or ATA come up with what position they advocate as being the position of all members? Many CI members with professional RSI platforms and a 2-team approach do believe and perform criminal trial proceedings that can be carried out with adjustments or a hybrid approach of in-person/RSI, if the need arises.

Hi!

Thanks so much Andrea for your article and a subject that touches my heart of the ex-Director of Language Policy in Mexico at the INALI and present trainer of aspiring interpreters in Mexico’s indigenous languages, many of which are of common concern to both Mexico and Guatemala and in the U.S. when immigration and other concerns arise and, guess what…?? not enough interpreters or resorting to relay interpreting. I hope you will write to me – lots to discuss – I am a member of NAJIT, ATA and AIIC, so you should have no trouble reaching me, abrazos.

Andreea, thank you for taking the time to write the thoroughly interesting article. You describe an important aspect of the situational issues: That those who interact with our profession often have a limited understanding of the complex nature of what we do. You observe that this is reflected in terminology misunderstood by the public, which may then carry to set-up in a courtroom because one interpreter is “resting” as the other works. Another is that the professionalism on the part of freelance interpreters not recognized, but misconstrued to be motivation for higher pay based on more hours rather than on fair compensation for trained skill and ongoing development, and equal access through language access, among some other issues.

Thank you for such a perspicacious, perceptive and informative article. If I may transgress, the Bronx Family Court uses a Kaqchikel interpreter that is fluent in English and lives in Pennsylvania. I understand he is not a native speaker but he has a good grasp of the language because of his work in Anthropology. His name is Donald Cheney.