27 Nov A Judge’s Discretion

Early on in my interpreting career, I learned an important lesson: the Judge is the king or queen of the courtroom. What they say goes. This means that as interpreters, we should address the judge when we need anything. And we do need things, on occasion! Perhaps the prosecutor speaks so quickly that we cannot keep up, or we must seek clarification of a term. In that instance, rather than simply telling the prosecutor to slow down, we defer to the head honcho in the courtroom: the Judge.

“Your Honor, the interpreter is struggling to keep up with the pace of the prosecutor,” we might say. That on its own may be enough for the judge to take the reins and request that the prosecutor slow down. (Beware, though: that darn prosecutor will likely speed up ten seconds later. Habits are very hard to break, and we interpreters can practice dealing with tricky speakers at home so that we don’t have to rely on others changing their speech patterns.)

Here’s the issue with the courtroom hierarchy, though. Judges aren’t always aware of what interpreting involves. Judges are bogged down with a million things, and they don’t have the time necessary to understand the ins and outs of interpreting. They are often monolingual and may not even be aware of all the possible misinterpretations and challenges that can arise.

One day in a Pennsylvania courtroom, my teammate and I were interpreting for a witness. This was still early on in my career, and I was working with a more experienced senior interpreter. We interpreted the witness’s testimony, and I also interpreted courtroom commentary. There was a lot of commentary, because this was a divorce case between two pro se litigants. They were acting as their own attorneys but without any understanding of the law. The judge had his hands full with the angry soon-to-be ex husband and wife shooting accusations back and forth across the room.

Then came the moment that I will always remember: I had been interpreting all the commentary, going by the standard I often apply when deciding how to proceed in a given interpreting situation: what would be understood if the witness spoke only English? I was interpreting everything that was said, out loud so the witness could hear it, because an English-speaking witness would have heard everything, too. I continued interpreting… until my senior teammate said I didn’t need to, asked the judge, and the judge asked me to stop.

Then came the moment that I will always remember: I had been interpreting all the commentary, going by the standard I often apply when deciding how to proceed in a given interpreting situation: what would be understood if the witness spoke only English? I was interpreting everything that was said, out loud so the witness could hear it, because an English-speaking witness would have heard everything, too. I continued interpreting… until my senior teammate said I didn’t need to, asked the judge, and the judge asked me to stop.

According to the judge, his conversation with the pro se litigants constituted a sidebar to which the witness should not be privy. By my ceasing to interpret, we would therefore shield the witness from hearing what should be kept private.

However, there were several things the judge was not taking into consideration. First and foremost: the witness likely did understand some English, as witnesses often do. So, if he wanted to keep things private, he should call an exclusive sidebar, just as you would in the presence of an English-speaking witness.

The judge was probably also unaware that he was asking my teammate and me to break our code of ethics, which says that we interpret everything that is said, exactly as it is said.

Unfortunately, my teammate was also unaware of the intricacies involved, and I was too new to stand my ground, even though I felt that being asked to stop interpreting was the wrong thing to do.

Ten years later, I would change my actions and speak up. I would state for the record what my code of ethics asks of me and why.

In all likelihood, the judge would have agreed once he had had the chance to understand all the elements involved. This has happened to me before; once, a judge actually thanked me for informing her of the need for an interpreting team. She had no idea that it went against best practices to have a single interpreter for a full-day criminal trial. Once I advised her of this, she thanked me profusely (not before I was driven to the brink though, interpreting by myself and completely exhausted).

A lot of my most challenging interpreting moments happened right at the beginning of my career. I had the training to know what the standards of practice should be, but I didn’t always know how to practically implement them, especially when working with other interpreters who did not seem to know our code of ethics and judges who didn’t know what our profession entails.

The important takeaway is that if we can state clearly what our best practices are and why, usually judges will understand, and you’ll have helped push interpreting proceedings onto firmer ground, not just today but for years to come.

At the very least, even if the judge still overrules you, you can rest easy knowing you’ve done your due diligence.

At the very least, even if the judge still overrules you, you can rest easy knowing you’ve done your due diligence.

Have you ever been asked to do something that was professionally inappropriate? If so, use the comments to tell us how you dealt with it. And if you need a refresher, check out the NAJIT Code of Ethics and Professional Responsibilities!

Athena Matilsky fell in love with languages the year she turned sixteen. She majored in Spanish interpreting/translation at Rutgers University and also studied French. After graduation, she taught elementary school in Honduras and then returned home to begin freelancing as a medical and court interpreter. She later became a staff interpreter for the NJ judiciary. She has gone on to earn certifications as a healthcare interpreter and a federal court interpreter for Spanish and as a court interpreter for French. Most recently, she received her Master’s Degree in Conference Interpreting from Glendon at York University. She currently works as an interpreter and teacher, training students to acquire the skills necessary to pass state and federal interpreting exams. When she is not writing or interpreting, you may find her practicing acroyoga or studying French. Website: www.athenaskyinterpreting.com

Athena Matilsky fell in love with languages the year she turned sixteen. She majored in Spanish interpreting/translation at Rutgers University and also studied French. After graduation, she taught elementary school in Honduras and then returned home to begin freelancing as a medical and court interpreter. She later became a staff interpreter for the NJ judiciary. She has gone on to earn certifications as a healthcare interpreter and a federal court interpreter for Spanish and as a court interpreter for French. Most recently, she received her Master’s Degree in Conference Interpreting from Glendon at York University. She currently works as an interpreter and teacher, training students to acquire the skills necessary to pass state and federal interpreting exams. When she is not writing or interpreting, you may find her practicing acroyoga or studying French. Website: www.athenaskyinterpreting.com

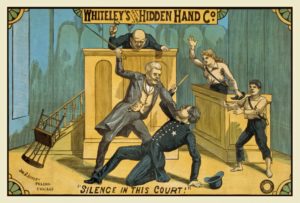

Featured photo: “Leipzig war crimes trials, first session” by Agence Rol, from the Gallica Digital Library, available under the digital ID btv1b53067692c; photo taken from the Wikimedia Commons; image in the public domain (Bibliothèque nationale de France, BnF). Text-body photos: “Vintage Hidden Hand Poster” by Dawn Hudson at PublicDomainPictures.net, photo in the public domain; “Cour martiale à Athènes, jugement du prince André de Grèce” by Agence Rol, Bibliothèque nationale de France, taken from the Wikimedia Commons, photo in the public domain.

Congratulations on this interesting article and for opening your heart to the rest of us who have suffered miserably under similar circumstances. Great, keep getting more and more academic credentials together with practical experience. Best wishes!

Thank you Georganne! Best wishes right on back to you. 🙂

Great Article, Athena! I feel responsible to know and follow the code of ethics and to help junior interpreters stand up for it. If we all found ways to uphold best practices and our code of ethics, it would benefit the courts and our profession. Over the years, I’ve come up with phrases I use to educate judges and attorneys about our profession. Most of the time, they appreciate it.

Thank you Reme! I agree that having already-prepared phrases can be quite helpful.

Reme: would you be willing to share the phrases that you’ve come up with? Thank you.

Thank you for sharing Athena,

It is a great professional and empowering reminder.

Happy Holidays!

Thank you Hemi! Happy Holidays to you too.

Hi All, yes great article, done that, being there! At the beginning, today I would say: Your honor, the interpreter cannot interpret a dialog’ especially an animated dialog

Hi Carmen,

I’m glad you enjoyed the article! I’m not sure what you mean about not interpreting a dialogue, as in fact in this case it was necessary for me to interpret the dialogue in order to uphold the code of ethics. But perhaps you mean that the conditions were not conducive to interpreting, which is certainly important to bring to a judge’s attention. Take care!

Thank you for sharing your experience and the importance of knowing how to implement the code of ethics. It resonates with many of us. These common situations linger in our minds until we can share them openly “righting” the wrong and learn from them. I will always remember what the trainers of my first court interpreting class said: “Nobody knows what you are doing, nobody. You need to educate the judge, the attorneys and the clients “.

Agreed!!! I remember receiving similar advice from my teachers, and it is SO true. We have to monitor ourselves because usually nobody else is (or other times EVERYBODY else is, but still without truly understanding what we are doing, nor how we should do it.) Take care!

Thank you for sharing your experience and the importance of knowing how to implement the code of ethics. I always ask myself why is it that the attorneys that are going to be litigators as well as judges, do not have courses as part of graduation, how to work with interpreters and made them aware of the code of ethics that we have to abide by?

Sylvia,

I agree. Unfortunately there is so much else for them to learn and working with interpreters is often not on the radar. However, more and more courts are putting such trainings into place, and they can’t come soon enough. Cheers!

One time I was interpreting in a C-section and I was hooked on that idea that “we must interpret everything that is said.” I was repeating the colloquy between the surgeon and his assistant. I was told to shut up. I objected, based on my code of ethics, but I complied. Later, the anesthesiologist, who coincidentally spoke English as a second language, took me aside and scolded me sharply. “You’re ignorant!” he said. That doctor never worked with me again. He explained to me that he didn’t want me to interpret a low-voiced private conversation that would potentially upset a patient who was having her belly cut open. And, in the operating room, just as in court, there is a king. I know that Moses said, “You shall do no injustice in court. You shall not be partial to the poor or defer to the great, but in righteousness shall you judge your neighbor. (Lev 19:15)” but in your example, not interpreting a sidebar is not “deferring to the great.” It is following court protocol, which is something even English speakers have to do.

I was once in the courtroom of Judge [REDACTED], who was known to be hard-nosed and maybe even a bully! This was a routine plea bargain. He told me to “Tell him [this, that, and the other thing]” When I balked, he screamed, “TELL HIM!” I have no appetite for jail food and thus prefer to not have someone like Judge [REDACTED] hold me in contempt, so I simply told the person in Spanish, “The judge says to tell you [this, that, and the other thing].” I probably needed a law degree and license to do so, but again, I had plenty of mass-produced food in my US Army days. I believe that I did what I needed to do to, once again, survive unscathed under pressure, without crossing the line into practicing law sans license.

That’s my story and I’m sticking to it!

Greetings from a retired Texas Licensed Court Interpreter in Taipei, Taiwan

Thanks for an excellent article!

You asked for examples of inappropriate requests, so here’s one that I suspect may be fairly wide=spread and difficult to resolve:

Not infrequently, some judges here will ask the interpreter to provide an ad hoc oral rendition of audio-recorded material in open court. When informed that the request is for an unacceptable practice, some judges get their backs up at what they perceive as a challenge to their authority and command the interpreter to do it anyway. Many interpreters find it hard to go against the implacable stance of a judge and they comply, while others (I, for one) refuse to obey the order on ethical grounds.

How have I dealt with it? Ideally, this problem leads to information sharing, as you suggest. If allowed, I explain that such a practice places the interpreter in the unacceptable position of being a witness and, more importantly, the result of such an action would mean that what is intended to be “evidence” would, under the circumstances, be mostly guesswork. (And if I happen to have it with me, which is unlikely, I give them a copy of the NAJIT position paper on the subject.)

In my experience, this “information sharing” tactic rarely works. Since this is a subject about which the judges and attorneys involved seem to have little knowledge, the interpreter’s position is rarely supported by them and it can turn into a stand-off. After presenting information to all concerned and being rebuffed, I’ve found that sometimes the only way to deal with the situation is by saying that, as an ethical interpreter, I must respectfully decline to follow the order and if further pressed, I will have to absent myself from the proceeding. It’s risky but at that point what other options are there? I can’t violate my oath to interpret “accurately and completely” and can’t put “guesswork” on the record as if it were solid evidence – an action I believe can have serious negative consequences..

I’m curious to know how the rest of you handle this problem!