18 Jan A Look at Translating for the Judiciary

Originally published in January 2015, this post remains relevant. Please enjoy.

On this blog, we dedicate a great deal of time and effort to the profession of interpreting for the courts. We tell stories, share experiences, propose new ideas, and issue calls to action. This week, let’s look briefly at some issues related to translating for the judiciary.

What’s the difference?

If somebody asks for the court translator, they probably mean to say interpreter, but we answer up anyhow. Nonetheless, given a few extra minutes, most of us would probably clarify that the interpreter works with spoken language, while the translator works with the written word. The difference becomes pretty important when we think of the tasks a language specialist would likely perform in a court setting.

Scope of practice

Court interpreters are often the first people that judges or attorneys think of when they need a document translated or an interview transcribed/translated. This is understandable, and even common practice, because most interpreters have been trained in the subject area and possess an excellent working knowledge of the terminology likely to arise. However, not all (in fact, relatively few) court interpreters work as translators. Why? The reasons vary, but are often based on a lack of confidence in the written word and a perception that translation is tedious. Similarly, a translator who specializes in the legal field may have little desire to work with the spoken word in court or depositions, for example. Although many interpreters and translators have dabbled in each others’ specializations, most do not hold themselves out to have expertise in both.

Specializing in legal translation versus translating for the judiciary

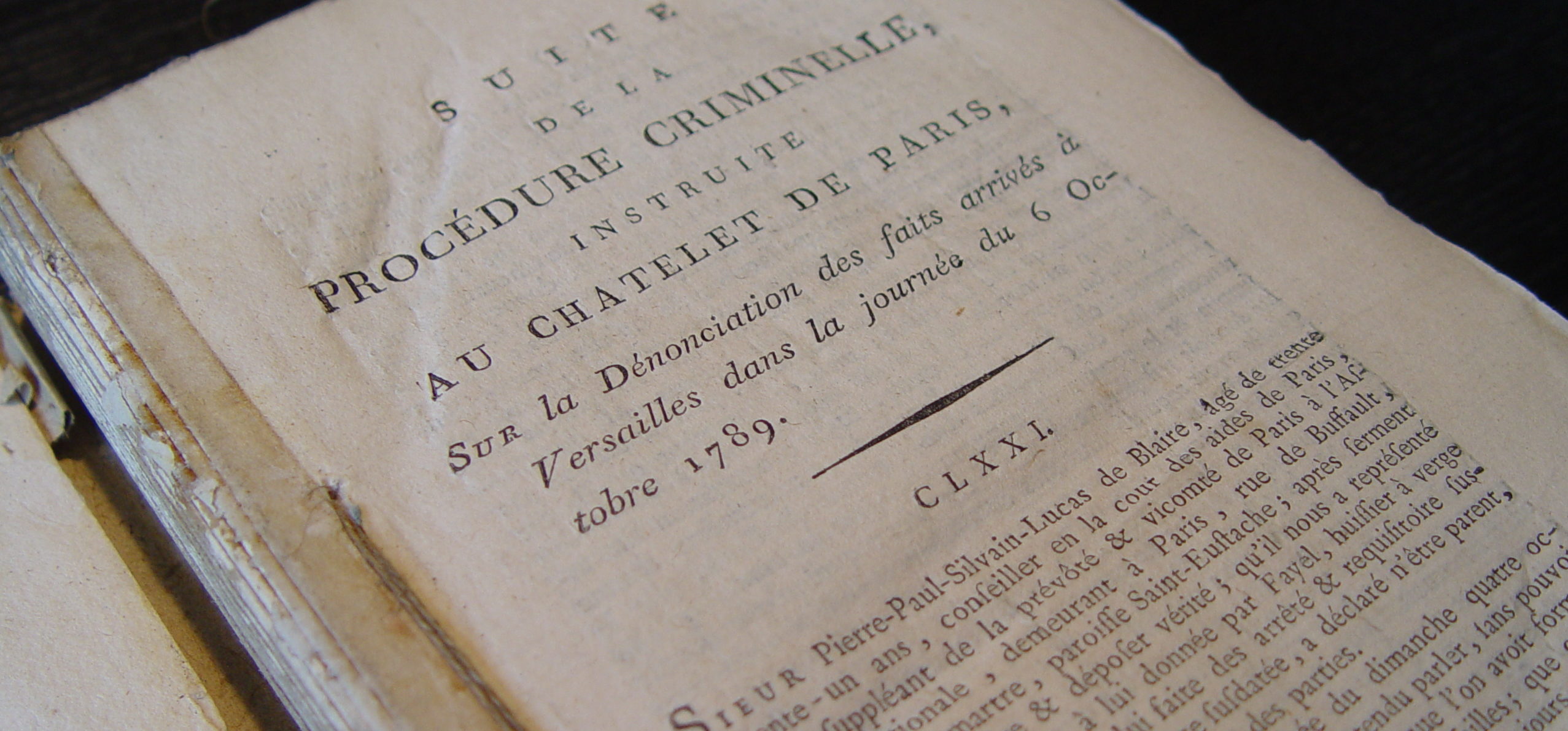

When we think of the courts, the criminal arena probably comes to mind first. Within that context, a typical request for a translation will be the transcription/translation of a police interview conducted in a foreign language, or perhaps a letter of confession or other similar evidence that must be translated into English to be included in the case record. This is where a court interpreter can easily apply his or her expertise in the spoken language to the related task of translation of conversations or informal writing.

The civil courts have a wide variety of translation needs, as well. Property titles and vital records are often requested for family law and probate matters, not to mention the typical civil suit. Here’s where many court interpreters could draw the line. Since complex legal documents such as these require a broader knowledge base that isn’t easily gained just by working in the courts, the interpreter may defer to a colleague translator when an attorney seeks their language expertise in this context. At the end of the day, the decision a court interpreter makes to accept or refuse written work will depend primarily on understanding his or her abilities and ethical duty to properly represent them to others.

On the other hand, we have those translators who specialize in legal translation. This field of work often stretches far beyond the typical lawsuit and ventures into international business and even politics and diplomacy. In other words, the work is not necessarily limited by the confines of a lawsuit or the courts. In my experience, translations performed for these fields are complex and often lengthy. Interpreters who work primarily for the judiciary are less likely to be approached for this sort of work on a typical day.

Can you be both an interpreter and a translator for the judiciary?

It took me many years of personal experience and discussions on this subject to come close to a definitive conclusion. I do believe it’s possible to do both, and that there are many talented colleagues who are able to perform well with the written word and the spoken word. The more poignant question is should we do both? Is it enough to be capable of each, or is the more professional answer to perfect one or the other?

It took me many years of personal experience and discussions on this subject to come close to a definitive conclusion. I do believe it’s possible to do both, and that there are many talented colleagues who are able to perform well with the written word and the spoken word. The more poignant question is should we do both? Is it enough to be capable of each, or is the more professional answer to perfect one or the other?

Let’s think of the bench and the bar. We all probably know attorneys who take on criminal defense and civil cases, but how competent are they? Are all of them equally good in both arenas? How about judges? After being assigned to the family law calendar for five years, can they perform at the same level of excellence when first reassigned to criminal matters?

The comparison gets more complicated, mind you, when we consider that the opinion of an expert witness (the translator) may not be as easy to analyze and correct as judicial performance or competent representation. It seems that the analysis is similar to the one we go through to decide which of our working languages is our A language… it often depends on the individual, the subject matter and a myriad of other factors.

Proceed with caution, even after passing the tests

I’m a firm believer in the value of a certifications and accreditations, but only as a starting or reference point. There is no doubt that experience and overall maturity in the profession should be considered when deciding whether to take on the task of translating a document for purposes of a court case. Moreover, we cannot assume that our experience in translating documents and transcribing/translating interrogations automatically gives us the expertise of our translator colleagues who work in the international court arena.

Just as the translating and interpreting professions are similar, but not the same, translating for the judiciary itself and for the legal professions are similar, but not the same. They can share many of their characteristics, but closer examination reveals differences that can be relied on when deciding who the right professional is for the job. Each interpreter, interpreter/translator and translator should proceed with caution when venturing beyond proven expertise, just as our ethics tell us.

This is meant to be a brief overview of some issues relating to translating for the judiciary. What do you think about practicing as both an interpreter and a translator? Any ideas on where to draw the line? If you work as a translator, are there certain types of judiciary work you prefer or would rather not take on? Continue the discussion below by commenting. We’d love to hear from you!

Janis Palma has been a federally certified English<>Spanish judiciary interpreter since 1981. She worked as an independent contractor for over 20 years in different states. Her experience includes conference work in the private sector and seminar interpreting for the U.S. State Department. She joined the U.S. District Courts in Puerto Rico as a full-time staff interpreter in April 2002. She has been a consultant for various higher education institutions, professional associations, and government agencies on judiciary interpreting and translating issues. She is a past president of the National Association of Judiciary Interpreters and Translators.

Contact: janis.palma@gmail.com

Read other posts by Janis Palma.

Thank you Janis.

A wonderful article. You are so right. I know some very good Romanian translators specialized in the legal field who would refuse to interpret in court even for a simple guilty plea. I have been doing both. About 25 years ago I started interpreting in court and in the last 10 years I have been translating extradition packages for the DOJ, to be sent to foreign countries. There is a huge benefit from doing that. Recently I translated an extradition package for more than a dozen defendants. After they were extradited, I had the fortune to interpret in federal court for all of them. Huge advantage, knowing every single detail of the case, including the sealed Indictment. There is a great benefit from doing both. Interpreting helps you think fast and find the right translation while translating helps you broaden your judicial knowledge.

Thank you for the article.

Lee

As usual, Janis, your posts are very helpful.

I always think of a translator and interpreter in the same way as a clinical physician who is a surgeon. I am sure it takes practice and time to be able to perform both functions. Therefore, I wonder: why not?

Thank you Lee and Salua for reinforcing my message based on your own experiences!