31 Oct Transcription In The Interpreting Profession: An Exciting Time To Be An Interpreter

We have all been there: tired and in need of a partner. Could there exist a machine that does the notetaking for me? I started to ponder about speech recognition many years ago when ASR (automatic speech recognition) was accessible via software (think Siri). I wondered at that time if one could use speech-recognition software to take down everything that is said during the course of one’s work as an interpreter. Even if this was possible, I also wondered how an interpreter would be able to use transcription, either in tandem with or independently from their notetaking. I knew that the technology wasn’t there yet. I scrapped the idea and continued taking notes the conventional way, with a pen and notepad. But what is speech recognition and what does it entail?

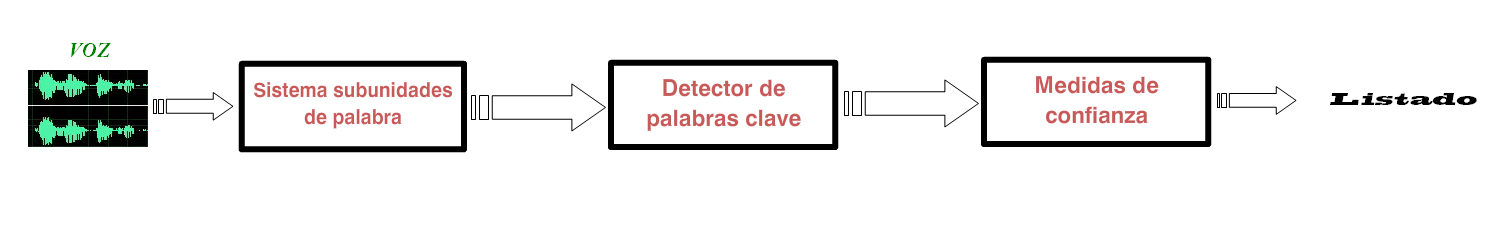

Speech recognition is the ability to detect and interpret spoken input[1]. Speech is often converted to text[2], and the ability to generate this text is promulgated by the use of AI. The text generated is commonly used for captioning or automated voice dictation[3]. Software engineers and scientists create models for the software to convert voice into a final product. As to AI and Natural Language Processing (NLP), I won’t bore you with terms such as machine learning, machine training, phonemes, or n-grams, but just know that this is a very complex process of taking a human’s voice (with its message) and transferring it to written text (preserving the message). As you would imagine, there are different challenges to arrive at a perfect and accurate text conversion from voice, but the technology has come a long way from making wild, and oftentimes funny, mistakes.

After the pandemic, I had some time to test what was possible with transcription. Some colleagues were rightfully incredulous about the idea that a machine could replace such an essential aspect of our work as interpreters. After all, machines are limited and still make mistakes. Still, I toiled and looked further into the matter. During my graduate studies at NYU, I noticed that Machine Translation, or MT, has come a long way in helping a translator with the use of CAT tools for their daily translation work. Through research into machine learning and machine training in my graduate program, I made an educated guess as to how far along speech-to-text software has come, both having similar applications with AI. I decided to test transcription and see if transcription could serve as a note-taking aid or even substitute notetaking.

The process of how to apply this idea pragmatically took various steps. First, I pictured in my mind how an interpreter could use speech-to-text technologies; this would require a computer or mobile device and a mic. Then I had to choose a speech-to-text software. There are many speech-to-text programs, but I settled on using the MS Word Dictate feature simply because it was already familiar to me. I spoke into MS Word Dictate, first in English and then in Spanish, and I obtained positive results. As I was speaking, I saw words appearing on the screen, in grey at first and then in black. Sometimes the word in grey was completely different from what I had said, and then a different word would appear in black. Sometimes an entire group of words would be different from the utterance, but by the time they were solid black, the machine had transferred what was said into text. This, I thought, was the machine learning and doing its algorithmic work into deciphering what was said.

The process of how to apply this idea pragmatically took various steps. First, I pictured in my mind how an interpreter could use speech-to-text technologies; this would require a computer or mobile device and a mic. Then I had to choose a speech-to-text software. There are many speech-to-text programs, but I settled on using the MS Word Dictate feature simply because it was already familiar to me. I spoke into MS Word Dictate, first in English and then in Spanish, and I obtained positive results. As I was speaking, I saw words appearing on the screen, in grey at first and then in black. Sometimes the word in grey was completely different from what I had said, and then a different word would appear in black. Sometimes an entire group of words would be different from the utterance, but by the time they were solid black, the machine had transferred what was said into text. This, I thought, was the machine learning and doing its algorithmic work into deciphering what was said.

The next step for me was to imagine how an interpreter could use the MS Word Dictate in various interpreting settings. I had the idea of connecting a microphone (lapel or table boom mic) to capture the audio from the LEP individual to send to the computer (or mobile device) in tandem with the use of conventional notetaking tools as a transcription aid, in case the software should “fail” due to poor audio quality or other complications in transferring voice to text. But how about remote interpreting? Initially, I thought of connecting a computer and a mobile device via an audio TRRS cable, but that entailed using two devices. Having sought solutions for remote simultaneous interpretation in my role as a staff interpreter for the State of New Jersey, I learned of a virtual-cable software to transfer sound between apps, just like a real audio cable. This solution, I thought, would work perfectly for video-remote interpreting. You can watch a video[4] I made on this topic on how to set it up on Mac computers.

Putting aside reservations about slang, regionalisms, and so forth, I went ahead and tested. Maybe I was overly optimistic, but my expectations were low. Would the machine be able to interpret different accents? I tested with diplomatic speeches in Spanish, and then I tested with real colleagues using a script. I was impressed; the results were better than expected. As I kept testing, I started to “learn” how to work with transcription, which some interpreters have coined as the “sight-consec” mode. It was a learning curve as expected but I kept practicing and testing. I didn’t want to overly rely on the technology, but I learned through this process that I needed some level of trust in the software. Over time, I started noticing that my consecutive interpretations got better with transcription; they were more fluent and natural. But I had to test this against conventional notetaking. I decided to test accuracy; hence I used The Interpreter’s Edge – Turbo by Holly Mikkelson with a consecutive exercise I hadn’t done. I tried taking notes with and without transcription. Once more, the results were impressive. Transcription was notably more accurate. Of course, future tests will need to check not only accuracy (including different languages, dialects, and environments) but also for didactical purposes, to build a new skill allowing people to work with transcription while being aware of the various pitfalls.

All in all, it is interesting to see how technology (with the use of AI) keeps evolving and gets better every day. Today, AI is being used in different applications, from creating works of art[5] to using applications in various forms of transportation. The European Parliament has taken a step further and introduced machine translation for parliamentary speeches[6], which makes me wonder what the future will look like for interpreters and our profession. I believe that we are stepping into a new frontier, and it is an exciting time to be an interpreter and translator. Will the interpreting profession be able to evolve with the changing technology landscape? If so, how? How will the legal interpreting profession be affected? All interesting questions.

[1] “Introduction – Training.” Training | Microsoft Learn, 2022, https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/training/modules/recognize-synthesize-speech/1-introduction. © Microsoft 2022, Accessed 10/17/2022

[2] “Introduction – Training.” Training | Microsoft Learn, 2022, https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/training/modules/recognize-synthesize-speech/1-introduction. © Microsoft 2022, Accessed 10/17/2022

[3] “Introduction – Training.” Training | Microsoft Learn, 2022, https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/training/modules/recognize-synthesize-speech/1-introduction. © Microsoft 2022, Accessed 10/17/2022

[4] Transcription for Consecutive Interpretation in Zoom Using Microsoft Word and Virtual Audio Cable, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y2DfGrXKz_0, accessed on 10/18/2022

[5] 6 Ways AI-Generated Art Is Changing the Future of Art, SIMONA TOLCHEVA, https://www.makeuseof.com/ways-ai-generated-art-changing-future-of-art/, accessed on 10/18/2022

[6] https://twitter.com/translation_eu/status/1549326940909309953, Europe In Your Language @translation_eu, 7/19/2022, accessed on 10/18/2022

David Proano Celi is a staff Spanish interpreter for the State of New Jersey. He has an undergraduate certificate in interpretation and translation from Hunter College and a Master of Science in Translation & Interpreting from New York University. He is also an amateur python coder. In his spare time, he enjoys playing various musical instruments and spending quality time with his wife and three cats. His website is interpretforme.com.

Main photo “Diagrama3 subunidades castellano” by Jordi R., from Wikimedia Commons, under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license. Body photo “Draagbaar dicteerapparaat ‘Rols 3’ met losse microfoon in zwarte koffer, objectnr 75310-A-D” from Apparatebau Stellingen GmbH, from Wikimedia Commons, under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

What an interesting article on how to keep using technology in the interpreting profession. I admire your willingness to try something new and to seek an application in the field of interpreting of what you learned about translation with the aid of machines. For me using transcription would be a learning curve! It is important that you pointed that out as well, that it does take time, effort, and dedication (also awareness of its pitfalls) to adopt this technology. Thanks again for sharing.

Hi Lillian,

Thanks for reading. I hope you enjoy trying it out on your own.

Thanks David. Great and timely article. After watching excellent your video footnote 4), I’m wondering if that setup can be done on a Windows computer.

Yes, it absolutely can. I use VB Audio VoiceMeeter “Potato” on Windows 10 and 11.

Hi Nicholas,

It can be set up on Windows as well as Linux if you feel adventurous. I will make another video for a Windows setup in the future on my Youtube channel. Cheers.

Thanks for the detailed post and the video! I’ve been using these tools for a while, too, but only in conference settings where it’s clear that I’m not violating client confidentiality. Colleagues should keep in mind that even if they are using the “dictate” function on Word, the signal is going out over the Internet …it’s not like it’s staying on ZOOM (,or zoom.gov). and their personal computers. Those servers may or may not be encrypted. And some courts may construe the AI transcription process as involving the “recording” of proceedings which is usually banned.

In sum, it’s a great, promising tool but one that needs to be used judiciously for now.

Hi Katty,

Thank you for sharing your thoughts, we might have a different point of view on a point you made but I appreciate your take. Thank you for reading.

Thank you for this article, David!

The use of an AI transcription software might be very helpful in the context of witness testimony during a trial.

Provided the tool is reliable, it would ensure we haven’t missed anything, since we do not want to interrupt the witness while they answer a question but want to make sure we don’t forget/miss anything.

Hi Hélène,

Thank you for your comment.