22 Dec A Look at Translating for the Judiciary

Almost three years ago, Jennifer de la Cruz delivered this informative piece. We hope you agree with us that it deserves another airing. Here it is and we look forward to your comments. Enjoy!

Jennifer de la Cruz © 2015

On this blog, we dedicate a great deal of time and effort to the profession of interpreting for the courts. We tell stories, share experiences, propose new ideas, and issue calls to action. This week, let’s look briefly at some issues related to translating for the judiciary.

What’s the difference?

If somebody asks for the court translator, they probably mean to say interpreter, but we answer up anyhow. Nonetheless, given a few extra minutes, most of us would probably clarify that the interpreter works with spoken language, while the translator works with the written word. The difference becomes pretty important when we think of the tasks a language specialist would likely perform in a court setting.

Scope of practice

Court interpreters are often the first people that judges or attorneys think of when they need a document translated or an interview transcribed/translated. This is understandable, and even common practice, because most interpreters have been trained in the subject area and possess an excellent working knowledge of the terminology likely to arise. However, not all (in fact, relatively few) court interpreters work as translators. Why? The reasons vary, but are often based on a lack of confidence in the written word and a perception that translation is tedious. Similarly, a translator who specializes in the legal field may have little desire to work with the spoken word in court or depositions, for example. Although many interpreters and translators have dabbled in each others’ specializations, most do not hold themselves out to have expertise in both.

Specializing in legal translation versus translating for the judiciary

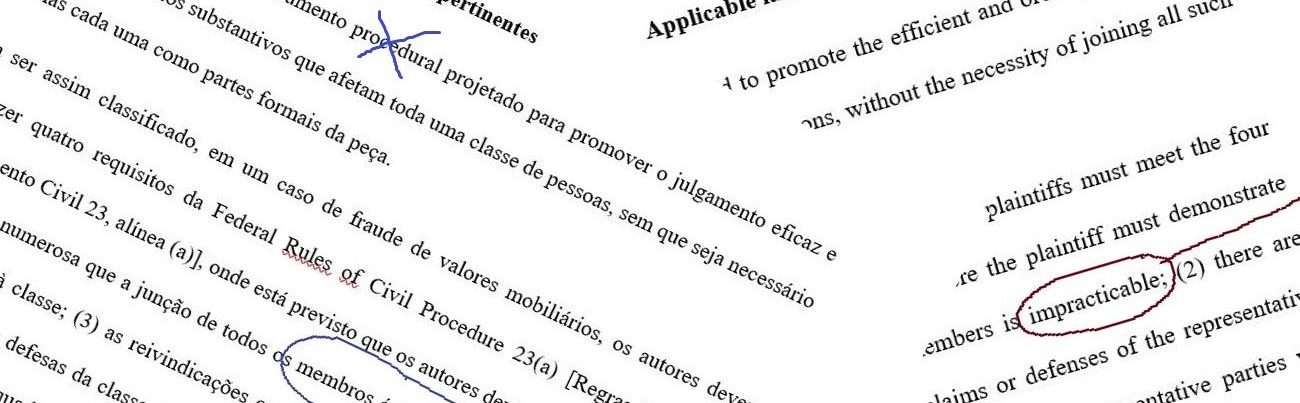

When we think of the courts, the criminal arena probably comes to mind first. Within that context, a typical request for a translation will be the transcription/translation of a police interview conducted in a foreign language, or perhaps a letter of confession or other similar evidence that must be translated into English to be included in the case record. This is where a court interpreter can easily apply his or her expertise in the spoken language to the related task of translation of conversations or informal writing.

The civil courts have a wide variety of translation needs, as well. Property titles and vital records are often requested for family law and probate matters, not to mention the typical civil suit. Here’s where many court interpreters could draw the line. Since complex legal documents such as these require a broader knowledge base that isn’t easily gained just by working in the courts, the interpreter may defer to a colleague translator when an attorney seeks their language expertise in this context. At the end of the day, the decision a court interpreter makes to accept or refuse written work will depend primarily on understanding his or her abilities and ethical duty to properly represent them to others.

On the other hand, we have those translators who specialize in legal translation. This field of work often stretches far beyond the typical lawsuit and ventures into international business and even politics and diplomacy. In other words, the work is not necessarily limited by the confines of a lawsuit or the courts. In my experience, translations performed for these fields are complex and often lengthy. Interpreters who work primarily for the judiciary are less likely to be approached for this sort of work on a typical day.

Can you be both an interpreter and a translator for the judiciary?

It took me many years of personal experience and discussions on this subject to come close to a definitive conclusion. I do believe it’s possible to do both, and that there are many talented colleagues who are able to perform well with the written word and the spoken word. The more poignant question is should we do both? Is it enough to be capable of each, or is the more professional answer to perfect one or the other?

Let’s think of the bench and the bar. We all probably know attorneys who take on criminal defense and civil cases, but how competent are they? Are all of them equally good in both arenas? How about judges? After being assigned to the family law calendar for five years, can they perform at the same level of excellence when first reassigned to criminal matters?

The comparison gets more complicated, mind you, when we consider that the opinion of an expert witness (the translator) may not be as easy to analyze and correct as judicial performance or competent representation. It seems that the analysis is similar to the one we go through to decide which of our working languages is our A language… it often depends on the individual, the subject matter and a myriad of other factors.

Proceed with caution, even after passing the tests

I’m a firm believer in the value of a certifications and accreditations, but only as a starting or reference point. There is no doubt that experience and overall maturity in the profession should be considered when deciding whether to take on the task of translating a document for purposes of a court case. Moreover, we cannot assume that our experience in translating documents and transcribing/translating interrogations automatically gives us the expertise of our translator colleagues who work in the international court arena.

Just as the translating and interpreting professions are similar, but not the same, translating for the judiciary itself and for the legal professions are similar, but not the same. They can share many of their characteristics, but closer examination reveals differences that can be relied on when deciding who the right professional is for the job. Each interpreter, interpreter/translator and translator should proceed with caution when venturing beyond proven expertise, just as our ethics tell us.

This is meant to be a brief overview of some issues relating to translating for the judiciary. What do you think about practicing as both an interpreter and a translator? Any ideas on where to draw the line? If you work as a translator, are there certain types of judiciary work you prefer or would rather not take on? Continue the discussion below by commenting. We’d love to hear from you!

Jennifer De La Cruz first became interested in learning Spanish in her college years, earning a Bachelor’s Degree in Spanish with an emphasis in linguistics from California State University at Fullerton. While interpreting and translating for the healthcare field, she earned certifications as a Court Interpreter for both the California and Federal Courts, later accepting a staff position with the California Trial Courts. Her passion for the Spanish language has become a thriving and satisfying career both in the fields of interpreting and translation, while her professional posts have allowed her to specialize in the highly challenging fields of law and medicine.

Jennifer De La Cruz first became interested in learning Spanish in her college years, earning a Bachelor’s Degree in Spanish with an emphasis in linguistics from California State University at Fullerton. While interpreting and translating for the healthcare field, she earned certifications as a Court Interpreter for both the California and Federal Courts, later accepting a staff position with the California Trial Courts. Her passion for the Spanish language has become a thriving and satisfying career both in the fields of interpreting and translation, while her professional posts have allowed her to specialize in the highly challenging fields of law and medicine.

Hi Jennifer,

My name is Ricardo Eva and have been interpreting and translating for the judiciary (U.S. Army´s JAG) since 1985 when one of my bosses, seeing how I was informally interpreting for Spanish speaking peers who had some difficulty understanding military instructions, decided that I was made to be a Military Linguist and guided me thru to become one.

On making the transition to become a U.S. Federal court interpreter, back in 2006 and armed with pretty much over 18 years of judiciary/jack of all trades translator and interpreter with the Department of Defense AND fully “armed” with school credits and letters of recommendation from several judges (at least two of them had since been promoted to General and Liutenant General and both went on to serve as legal advisors in the Pentagon) and letters from a myriad of civil and military attorneys I was truly SHOCKED to find that the U.S. Federal Courts DID NOT FIND ME QUALIFIED to interpret with them!!!

So, after much asking around, getting information, trying to figure out the WHY would the Federal Court system NOT accept my JAG background and Military Schooling I came to find out that I needed to be “tested” by them, to become “federally” licensed (?? which I thought I already was…)

Sorry, I´m digressing, back to the point…, I did this “test” that included both INTERPRETING AND TRANSLATING (I also have some thoughts about these “licensing tests” and HOW FAR AWAY THEY ARE FROM REALITY!) so I was, and always have been, under the impression that a Federally qualified Interpreter IS ALSO a Federally qualified Translator. Furthermore, I´m of the opinion that if we, and future generations, become interpreters and translators we SHOULD HAVE pride in our profession and our professional development and, therfore, always strive to improve our KSA´s and BE READY for whatever task we´re given, whether it´s translating or interpreting.

I am a certified court interpreter (Oregon, Spanish) and a Certified Translator (ATA ES into English, WA DSHS EN into ES). I have worked in both fields. In the last two years, I took a break from interpreting because of asthma and family health issues and focused entirely on translation. I developed a translation training program similar to some of the court interpreting training programs. It works. Anyway. Back to your question. I see a lot of court interpreters translating without any specific training in translation. Is that the right thing to do? They find it unacceptable to take on an interpreting job that a person is unqualified for under those guidelines, but not so much a translation job. Why is that? We need to open that conversation as well. This could be because translation training is not easily available in court trainings, and maybe court interpreters don’t get CE credits for translation training. I don’t know. But it is something we need to think of.

Court interpreting tests do not test translation. They are not even writing tests. They are English reading comprehension tests, if anything. And they certainly do not test Spanish writing. So writing training, particularly in copy editing using the Chicago Manual of Style, the book El buen uso del español and other style guides, would be in order. Besides, of course, translation training after that is done.

At this point I am not sure whether we should do both. I see schedule conflicts written all over the place with doing both. I have heard of court interpreters taking their laptops in and doing review of a translation during “breaks” in the court. I have been in court, and I have worked as a translator in my office. You just don’t have the same level of focus in both places. Are you really capable of doing your best when you don’t have the ability to give the translation work the focus it deserves? This is an issue.

Or saying “Oh, an interpreting job came up, so I will finish the translation and cut my sleep short.” Sure. But tomorrow, my work will not be as good. Does tomorrow’s client deserve that treatment?

These are issues we need to think about. I am not sure whether that is what you were thinking of, Jennifer. However, they were the ones that caught my attention. Are these ethics issues? Are they business practice issues? I don’t know.

Yours,

Helen Eby