26 Jul Qualis Lingua Personae

Experienced court professionals and many ordinary common citizens alike in both the United States of America and the United Kingdom are familiar with the centuries-long doctrine of “Habeas Corpus.” However, ever since the inception of the habeas corpus doctrine, we have never had a complementary concept to affirm and confirm the language(s) of the person who appears before the Court following a habeas corpus proceeding.

Experienced court professionals and many ordinary common citizens alike in both the United States of America and the United Kingdom are familiar with the centuries-long doctrine of “Habeas Corpus.” However, ever since the inception of the habeas corpus doctrine, we have never had a complementary concept to affirm and confirm the language(s) of the person who appears before the Court following a habeas corpus proceeding.

It is my belief, through my ongoing professional experience as a working California State Certified Court Interpreter, that the missing twin doctrine to habeas corpus is a novel concept that I call “Qualis Lingua Personae,” according to which the Court would be compelled to affirm and confirm the language of the parties appearing in court following a habeas corpus proceeding. “Qualis Lingua Personae” simply means (in Latin) “the Quality of the Language of the Person.”

For the doctrine of “Qualis Lingua Personae” to be applied effectively, the Court cannot merely rely on casual statements by either counsel or a court clerk, or a court interpreter for that matter, on what the language of the person appearing before the Court is under habeas corpus. The Court should be compelled to ascertain the languages of the parties appearing in Court by way of a judicial oath either in open court or in writing under my proposed novel doctrine of “Qualis Lingua Personae.”

In circumstances where any individual party might claim to have “two indivisible native languages,” the Court should once again, by means of an oath (under the doctrine of “Qualis Lingua Personae”), require such an individual to elect which of those two languages that individual will use throughout the entire duration of any particular set of proceedings that are related to a single case.

A judicial oath for the purposes of guaranteeing the application of the doctrine of “Qualis Lingua Personae” could theoretically be crafted and integrated into existing opening oaths in a variety of ways across all jurisdictions in the United States.

For example, a judge (or a justice in a court of last resort) could ask a respondent:

1) Do you swear to tell the truth and nothing but the truth?

2) Do you swear that you speak and understand and intend to use “Language X” throughout the entire duration of the court proceedings pertinent to this case and only this case?

First of all, in the example above, oath 2) is automatically clearly and firmly supported by oath 1).

Secondly, the two oaths together diminish the likelihood of any party attempting to claim discrimination against them based on language, culture, race, ethnicity, tribe, and/or national origin.

Secondly, the two oaths together diminish the likelihood of any party attempting to claim discrimination against them based on language, culture, race, ethnicity, tribe, and/or national origin.

Thirdly, both oaths eliminate the possibility of either “judicial imposition” or “administrative imposition” of any particular language(s) on a party appearing before the Court.

And finally, both oaths administered universally to all parties close the door in our jurisdiction to English-speaking parties who might strangely elect to address the Court in a language other than English.

Since I live and work in the epicenter of technological innovation (the San Francisco Bay Area and neighboring Silicon Valley), I often wonder why it is that no new products and no new services emanate from the justice sector (or judicial sector) as we see in the tech, health, commercial, educational, or industrial sectors.

Although “access to justice” is a prominent goal in the justice sector, the overarching professional principle and purpose of all sectors of society (particularly in transactional events between the State and individuals) should be the idea of “access to service.” The “Qualis Lingua Personae” doctrine could undoubtedly be adopted and integrated into the processes of other professional service sectors under the heading of “primary service language” (or “primary care language” in the health sector).

Patrice Binaisa, Patrice Binaisa (B.A., 1983, Spanish, Middlebury College, Vermont) is a Ugandan American Spanish/English court interpreter (State Court certified in California since 2013). He speaks Luganda, English, Spanish, French, Portuguese, and Mandarin. He is also an actor and voice actor. Having left Uganda in 1974, Patrice and his family first found asylum in the U.K., and then moved to the U.S.A. in 1977. His dear late father, Godfrey L. Binaisa QC, was Uganda’s first attorney general (1962-67) and Uganda’s fifth president (1979-80). A member of the USCF (United States Chess Federation) – with a ranking of 1340 –, Patrice is currently studying the Benko Gambit. He has worked as contract interpreter and in U.S. Immigration Court in California, and as a staff interpreter in Northern California State Courts. Find Patrice on IMDB or on Facebook, or write to him at adjustice7@yahoo.com.

Patrice Binaisa, Patrice Binaisa (B.A., 1983, Spanish, Middlebury College, Vermont) is a Ugandan American Spanish/English court interpreter (State Court certified in California since 2013). He speaks Luganda, English, Spanish, French, Portuguese, and Mandarin. He is also an actor and voice actor. Having left Uganda in 1974, Patrice and his family first found asylum in the U.K., and then moved to the U.S.A. in 1977. His dear late father, Godfrey L. Binaisa QC, was Uganda’s first attorney general (1962-67) and Uganda’s fifth president (1979-80). A member of the USCF (United States Chess Federation) – with a ranking of 1340 –, Patrice is currently studying the Benko Gambit. He has worked as contract interpreter and in U.S. Immigration Court in California, and as a staff interpreter in Northern California State Courts. Find Patrice on IMDB or on Facebook, or write to him at adjustice7@yahoo.com.

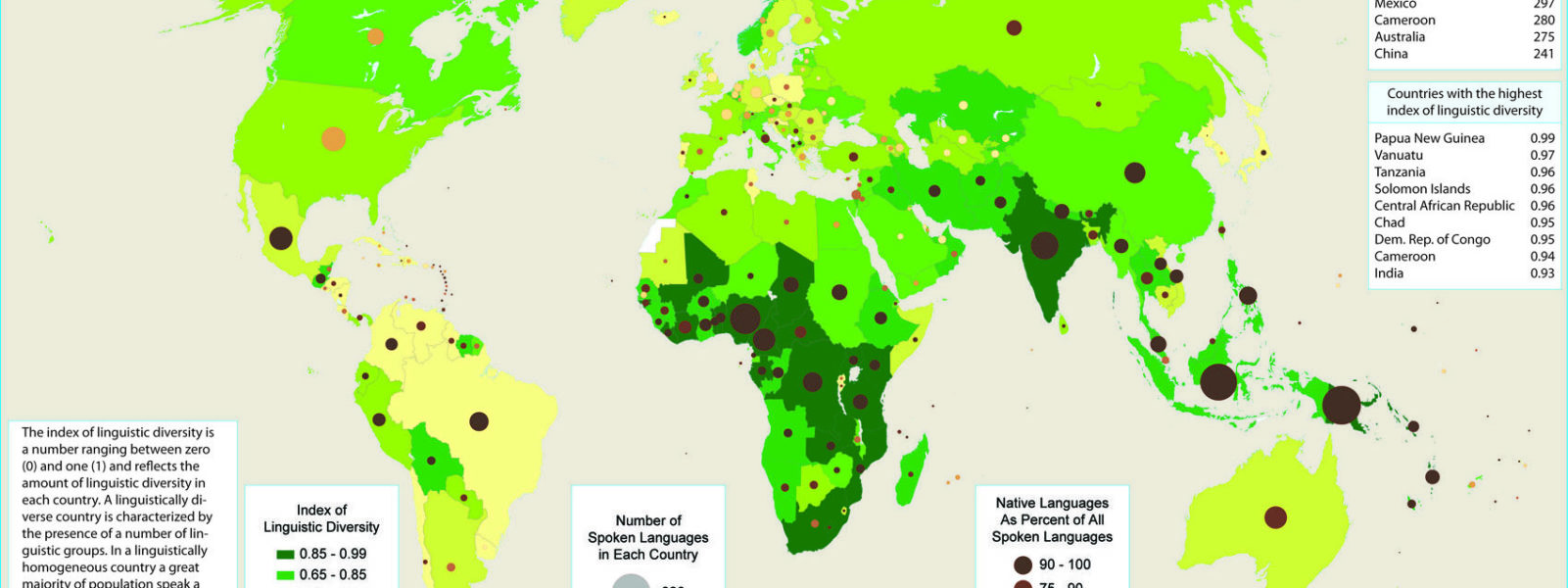

Main photo taken from “Diversidade linguistica do Mundo” by Kazimierz Zaniewski at OpenEdition Journals no. 9 (2010), under the CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license. First body photo taken from “Juridique et judiciaire, une différence entre ces deux termes ?” by Koloina Rasoahoby at STILEEX: Maths, Data & Information, under the CC BY 4.0 license. Second body photo taken from “Le secret professionnel du magistrat,” “Audience correctionnelle au Palais de Justice de Paris,” in Respecter et intégrer les aspects légaux liés à la protection et à l’accessibilité des données professionnelles at Université de Paris 1 (Panthéon, Sorbonne), Université Numérique Juridique Francophone, under the CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 license.

A very good idea and proposal, elegantly expressed. Muito obrigada

Good article and a good cause but the translation from Latin should read: “What is the person’s language?”

Interesting proposal but I forsee difficult implementation. Code switching is a constant issue facing interpreters. But it is what it is and not much can be accomplished to avoid that just by issuing an order from the bench.

(I do not want to even get started here on the issue of Spanglish)

There are other issues here. For example I have found that while a defendant in a German case may ask for an interpreter, it then turns out that he/she speaks perfectly good English, but would prefer that the case proceeds in English and just want to have a German interpreter present on “standby” just in case he/she does not understand some technical or legalize expression. Of course most courts prefer that the interpreter remain on standby because it speeds up the proceeding avoiding consecutive interpretation in many cases. (And I do not even want to get here into the issue of German as a language when it turns out the defendant may only understand and speak Platt, Frisian or such varieties as backwoods Bavarian dialect all of which are “German”.

Of course a Scottisch dairy farmer speaking English has just a heck of a time understanding a cowboy from Abilene Texas, yet both may rightfully claim to speak English.

Being a court interpreter is a lot of fun sometimes in just sorting all this out.

Cheers, Carlos Benemann California Court Certified and Registered Spanish/German Interpreter. since time immemorial.

An interesting idea. It might prevent attorneys from asking courts to assign Spanish interpreters to assist Portuguese speaking defendants..

Great piece, Patrice. Thank you for provoking your readers to think outside of the box. Of course, the courts will never change and progress at the same pace as the technology field because it is in the nature of the law and the legal institutions to change slowly, very slowly. That doesn’t mean we should not be thinking about–and proposing–changes.

Thank you for posting this. I think it is an incredible idea. Perhaps it could be developed in a way that also addresses the concerns Carlos mentioned while still achieving the desired goal. But either way, you have blown my mind – right out of its box.

Hello Patrice,

I am with Carlos Benemann in that code switching is a reality that we can’t change. I recommend Ernest Ni~o presentation just for additional information. I enjoyed it and it does not necessarily address or suggest which approach is better but I liked the session and it is related.

Presenter: Ernest Niño-Murcia

Language: SPANISH

Level: All Levels

Saturday, June 3, 10:30 AM – Noon EDT

Session Description: When is a sentencia not a sentence and why is it inappropriate to interpret asalto as assault? U.S. Spanish or so-called “Spanglish” is a reality in the everyday practice of interpreters in the courts who must, at a minimum, have a passive understanding of these terms to be able to operate effectively. The stakes of potential misunderstanding are particularly high when it comes to interpretations of legal terms influenced by a similarity with English terms, which can sometimes have very different meanings. This workshop will present participants with a brief overview of the topic before allowing them the opportunity to grapple with these potentially tricky terms, all within the context of the need for accuracy and the ongoing evolution of language.

Objectives: Participants will be able to identify Spanglish false cognates to avoid in legal interpreting.

Hi Everybody,

Thank you all for your wonderful and enlightening comments on my article! I apologize in advance for not being able to respond to all of you individually.

Nevertheless, please kindly continue to ponder my article and continue to freely comment on it at will.

Your insightful comments have also inspired me to address some points that I hurriedly didn’t address in my original published text of the article. I will try to briefly address some of those equally important points now in this first comment of mine.

1) The Latin term “Qualis Lingua Personae” can either be conceptually translated as “The quality of the language of the person” or alternatively as “What is the language of the person”. I like the first rendition in courtroom scenarios involving attorneys’ objections. An attorney could invoke “Qualis Lingua Personae” as a valid objection during legal arguments before the Court, in order to for example advise the Court that his or her client’s linguistic status was ignored. Counsel’s client might be “non-verbal and non-vocal”.

2) The reason why a new complementary doctrine of “Qualis Lingua Personae” is paramount, is because “Habeas Corpus” doesn’t even clarify for us if we have a “corpus vivus” or a “corpus mortuus” before the Court. We need to know if it’s a living “corpus loquens” or not.

Thank you all once again for your comments!

Thank you, Mr. Binaisa. I love your proposal, for the many reasons you state and acknowledging the replies that expand on the subject. One of my personal pet peeves is the issue of unqualified attorneys trying to wave the interpreter off, such as “my client doesn’t really need an interpreter”, to which I usually replied along the lines of, “with all due respect, counsel, that is your client’s decision, not yours.” Almost in every instance, when I turned to ask the client, “¿necesita un intérprete?”, the answer would be “si, por favor”. I am sure we are all well familiar with different expressions of this. Thank you again!