Letter from the Editor: Proteus 2017/18 Winter Volume XXX Issue No 2

Proteus

Issue: 2017/18 Winter Volume XXX Issue No 2Table of Contents

Editor's Corner

Letter From the Editor

By Arianna M. Aguilar

Greetings! I hope that last year was a good one, and that this year will also be full of positivity and change for the better.

Personally, I am grateful and happy to be newly appointed as Editor-in-Chief of Proteus. For the past several years I have worked as an editor for Proteus under the direction of Dan Decoursey. I learned a lot from that activity and hope to continue to learn in my new role.

I would like to thank Andre Moskowitz and Kathleen Shelly who have done a wonderful job working on Proteus as editors. I am also thankful to have worked with Gladys Matthews and Susan Cruz. I especially appreciate the feedback and opinions I have received, and feel blessed to have the opportunity to work with such experienced colleagues.

This issue of Proteus has several interesting articles including one about Advocacy Day by Zeng Zeng Yang that talks about how NAJIT members from the 2017 Annual Conference in Washington, DC went to the Capitol to advocate for the interpreting profession.

We also have two book reviews, an article about sole proprietorships’ taxes, and a brief article about the importance of continuing education. Another piece is a discussion on the importance of minimizing one’s foreign accent when interpreting into and speaking a foreign language. And yet another article is about how we interpreters are affected by vicarious trauma and provides strategies to address this issue and mitigate its effects.

I have enjoyed working on this issue and hope you will enjoy reading it. I would also like to state that we are constantly looking for new contributions so do not hesitate to send me new submissions or contact me at proteus_editor@najit.org with any questions you may have.

Again, thank you to everyone for your support of NAJIT and our profession.

Warm regards,

Arianna M. Aguilar

Meet the Editors

Editors of Proteus 2017/18 Winter Volume XXX Issue No 2

Arianna M. Aguilar has a degree in communications and has been interpreting and translating since 1999. She has been a certified court interpreter in North Carolina since 2005, and master certified Spanish-language court interpreter since 2013. She is president of Latino Outreach Consulting of NC, Inc., a translation and consulting agency, and is a published author. She has given presentations on a range of topics at both NAJIT and American Translators Association (ATA) conferences.

Andre Moskowitz is a Spanish-language interpreter certified by the United States federal courts and the California state courts. He is also a Hispanist, lexicographer and dialectologist, who has published a series of works in the areas of Spanish lexical dialectology and Spanish lexicography.He taught English in Colombia and Ecuador for four years, and holds a B.A. in humanities from Johns Hopkins University (1984), an M.A. in translation studies from the City University of New York Graduate Center (1988), and a second M.A. in Spanish with a minor in Portuguese from the University of Florida (1995). He is certified by the American Translators Association as a Portuguese>English, Spanish>English and English>Spanish translator. He is also an editor for Intercambios, the newsletter of the Spanish Language Division of the American Translators Association (ATA).

Kathleen Shelly a Delaware and Maryland translator and interpreter certified by the Consortium for Language Access in the Courts, has worked as a professional interpreter and translator for the past 18 years. She has a master’s degree plus doctoral work in Latin American literature from the Ohio State University, and was a college professor for 12 years. A member of NAJIT since 2005, she has served as Secretary of the Board of Directors and a co-editor of Proteus,and always welcomes the opportunity to work to promote the interpreting profession. She is also a member of ATA and Delaware Valley Translators Association.

Feature Articles

Trauma Among Interpreters

By Charlotte Henson

Day after day, interpreters devote themselves to becoming the spokespersons of witnesses, refugees, politicians, victims and patients. Not only do interpreters listen to their client’s voice, they also immerse themselves in the speaker’s cultural background, life and storyline, regardless of how distressing it may be. Additionally, the mandatory use of the first person, I/we, while interpreting also makes it nearly impossible for the interpreter not to vicariously experience the client’s trauma on a deeper level, and may even trigger memories of painful past events. Therefore, when interpreting traumatic events, interpreters inevitably put themselves at risk for developing psychological distress. Like many other emotionally demanding jobs, interpreters are in fact very likely to experience intense emotions such as fear, anger, confusion and anxiety. It is thus possible in this context to refer to vicarious trauma, which is defined by Robert T. Muller (2013) as follows:

“Vicarious trauma can be best understood as the absorbing of another person’s trauma, the transformation of the helper’s inner sense of identity and experience. It is what happens to your physical, psychological, emotional and spiritual health in response to someone else’s traumatic history. Vicarious trauma can affect your perception of the world around you and can result in serious mental health problems such as depression, anxiety and addiction.”

In order to raise awareness about the risks associated with this field of work, I decided to conduct a study regarding the effect on interpreters of interpreting traumatic events on a regular basis. To this end, I gathered testimonies from 12 interpreters in one-on-one interviews, six of which were conducted in Paris, three in Geneva and three via Skype. My survey sample was made up of four men and eight women: seven from North Africa and the Middle East (Algeria, Tunisia, Lebanon and Syria), four from Europe (Italy, Spain, Romania and Belgium), and one from Russia. In this survey, eight of the 12 interpreters had interpreted detailed descriptions of acts of torture; six had interpreted for victims of terrorist attacks; and five had dealt with subjects such as famine, hostage-taking, rape, abuse and sexual assault. In order to conduct a comparative study, the interpreters were divided into two groups: the high-frequency group, made up of eight interpreters facing high exposure to traumatic content; and the low-frequency group, made up of four interpreters facing low exposure to traumatic content.

Seven out of Eight Interpreters are Affected by Traumatic Contents

My study shows that seven interpreters from the high-frequency group acknowledge being affected by the negative and traumatic content they have interpreted in the past; compared to only one interpreter from the low-frequency group. Interpreters from the low-frequency group claimed they have experienced temporary symptoms such as discomfort, fear or anger. However, symptoms described by the high-frequency group appear to have a more significant and long-lasting impact. As a matter of fact, half of the participants from this group report having sleep disorders and/or excessive rumination over past events.

Thinking back on her own experience interpreting in Syria one of the participants recalled the following: “Recently, I had to interpret for Syrian women in refugee camps… It was the most horrific thing I ever had to do in my life […] I had nightmares about it for months, re-imagining everything they had told me.”

Three other participants mentioned feelings of sadness, as well as physical and mental burnout. Feelings of guilt were mentioned by two interpreters, particularly when recalling interpreting in countries affected by famine. Angry outbursts were mentioned by two interpreters.

Impact on the Quality of Interpretation

Further investigation showed that four interpreters from the high-frequency group believe that when interpreting in a judicial context the fate of their client depends heavily on their own performance. As one participant explains, “Their fate is entirely in my hands, since I am the one who passes on what they have to say… it only adds to the stress and pressure […] It all comes down to me. The person can be released thanks to a good interpretation, and that same person can also be sentenced because of a bad interpretation.”

Therefore, the stress induced by the sense of responsibility towards others is significant. In addition to possible physiological consequences, repeated exposure to stressful working situations may cause higher psychological risks such as feelings of loss of control, overexertion, tension and exhaustion. Furthermore, two other interpreters explained the negative effects that interpreting for a cause they do not support can have on them. One of them revealed that she became aware of the fact that the quality of her interpreting decreased noticeably when interpreting for a misogynist politician: “I had so much trouble interpreting for this misogynist MP. I knew I wasn’t being impartial. I knew people could hear the anger in my voice… I couldn’t help it. At first, I tried to stay neutral, but I couldn’t.”

Coping Strategies

In order to reduce the negative effects caused by exposure to traumatic content, the interpreters who participated in this study shared the different coping strategies they use on a daily basis. In the survey, most interpreters stated that they released negative feelings through sports activities. The second most commonly used strategy is to share one’s experiences with the social or family circle.

However, several interpreters mentioned the additional challenge caused by confidentiality when interpreting for victims of trauma: “When you’re on a mission, not being able to talk about it with your family is very difficult. You can’t say anything on the phone because everything is under surveillance. With all that we have seen and heard, not being able to vent raises the levels of anxiety and frustration that we feel.”

In addition to this stress, another participant mentioned how the constant ability to adapt that interpreters must demonstrate may trigger a state of extreme physical or mental fatigue: “When we go out on a mission for one or two weeks, it is like a window opening to another world, and we are not always ready to adapt to this new environment. These constant social adjustments are what can be truly traumatizing… It is about living in different cultures, and finding ourselves again once we come back.”

...none of the participants were aware of any kind of support system available to them in their work environment

A Lack of Support

Despite the fact that seven interpreters from the high-frequency group admitted being affected by these situations, none of the participants were aware of any kind of support system available to them in their work environment. In fact, several of them expressed their disappointment with the absence of support. In total, four participants from the high-frequency group expressed the need to get help.

Several interpreters spoke of colleagues who have suffered from such extreme burnout that they are currently unable to work, and 100% of the participants stated that they never received adequate training to cope with interpreting traumatic content.

Lastly, the fact that three participants from the high-frequency group have been or currently are attending individual therapy is additional evidence of the need to heighten awareness of the risks that interpreters are exposed to. In this regard, this study seeks to emphasize the need to provide further training to interpreters as well as adequate support and counseling services. Implementing team supervision focused on the support and improvement of interpreters’ working conditions is an option that should also be considered. Providing supervision would not only give interpreters the opportunity to collectively explore their own professional experiences, it would also allow them to discuss complex work issues and mobilize new resources to face them.

[Charlotte Henson is a Franco-American psychologist specialized in work-place related trauma. Her areas of expertise include vicarious trauma suffered by emergency service professionals (fire fighters, paramedics, etc.) and professional interpreters working with victims of violence, crime, torture, and other forms of abuse. She based her Master’s thesis on a field study she conducted which included United Nations Interpreters in Geneva and Paris, as well as certified Court and Police Interpreters. She is also experienced in real-time critical assessment and strategic response to victims of traffic accidents, attempted suicide, loss of family members, serious injury or medical emergencies.]

The views and opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official position of NAJIT.

Does Accent Really Matter?

By Jeff Martin

If I were a native speaker of Russian, I would probably have the following linguistic attributes in the Russian language: proper grammar, extensive vocabulary, superb comprehension of both the spoken and written language, the ability to communicate freely with other Russians. Above all else, when I spoke Russian, I would sound like a native speaker. My accent and pronunciation would be similar to that of my fellow countrymen.

What if I possessed all of the foregoing attributes except accent and pronunciation? What if I spoke with an American accent, making it difficult for other Russians to understand me? It might even be difficult to convince people that I’m Russian. Let’s take it a step further. What if I became a Russian/English interpreter, yet still having the same issue with my accent? How qualified would I be in your opinion?

One of the first things I remember reading about court interpreting was the language standards that the candidate must meet before even considering taking the exam. One of those standards was to have achieved a native-like fluency in both languages. When I think of someone who has achieved a native-like fluency in English and Spanish, I usually picture a child of Hispanic immigrants, who either moved to the USA as a child, or was born here. His parents and possibly the entire family spoke mainly Spanish at home. They mastered English by learning it in school, and being constantly exposed to and having interaction with non-immigrants. In short, they grew up bilingual. They have the ability to sound like a native speaker of both languages. If they do speak with an accent, it is slight enough not to inhibit their speech. This is the level of sophistication that we should strive for as interpreters.

I once heard an interpreter say that accent wasn’t important. The ironic thing was that I barely understood her as she was speaking. This was during an interpreting workshop. Each one of us was asked to stand and introduce ourselves. When this particular lady stood and began to speak, I had to work hard to focus on what she was saying, often only understanding her words a few seconds after they were spoken- almost like the decalage that takes place during simultaneous interpreting, only this time I was having to interpret from English to English. This was a huge distraction to me, and made it difficult to understand her message. Instead, I was focused on understanding the words. Sound familiar? This is the opposite of what we are trained to do as interpreters: focus on the meaning of the message being spoken rather than merely the words.

Often when working with attorneys, I like to instruct them on how to utilize my services effectively. The easiest way to explain it to them is to tell them to use me like a cell phone. They speak through me to their clients. My job is to convert the message from the source language into the target language, maintaining the same register, emotion, and meaning without adding or omitting anything – sort of like a cell phone. What if when talking to a client on the phone, the message were to become distorted somehow? What if the voice the client heard was in a heavy foreign accent? If it were subtle, it probably wouldn’t make too much of a difference, but if it were moderate to heavy, part of the listener’s focus would be on trying to decipher the words. They would be at least slightly distracted.

Speaking with an accent poses different problems for the interpreter, depending on which accent they are retaining

Speaking with an accent poses different problems for the interpreter, depending on which accent they are retaining- English or the foreign language. Let’s first address some problems that the average American-born interpreter may face, assuming he learned the foreign language later on in life, perhaps in school.

If he learned the foreign language later in life, perhaps in school. When interpreting from English into the foreign language for the limited English Proficiency person (LEP) , it’s quite probable that the LEP may not understand certain parts of the message, due to either mispronunciation, slurring of words, or part of their focus being distracted away from the meaning from having to struggle to decipher words. Therefore, the response made by the LEP could very well be based on a basic misunderstanding of the original question.

In my opinion, we speak the language sounds that we hear in our minds. If we speak a foreign language while using the sounds of our native language, we listen to the foreign language from a biased standpoint. Most foreign language students in school are taught to read and write from the beginning, making it nearly impossible to speak without using the sounds of their native language. The following is an excerpt from my upcoming book:

By the age of five, most of us already know about 5,000 words. Around this age we begin school, and start to learn how to read and write, and use proper grammar.

When we learned the alphabet, we were taught to assign sounds of our native tongue to each letter or combination of letters, sounds that we had already learned how to produce. Those are the same sounds we can mentally “hear” while reading silently.

Compare this to the common classroom approach to learning foreign languages. The student learns the new alphabet on or about day one. If the alphabet uses Roman script, the student tries desperately to assign new sounds to letters that they have been pronouncing a certain way their whole life, which is extremely difficult. Most students have a natural tendency to pronounce the new alphabet with sounds of their native language, the only language sounds they have mastered. Once the alphabet is “learned,” the student proceeds to learn to read and write in the new language, but continues to pronounce the words using his or her native language sounds. Added to this almost unavoidable trap of mispronunciation is the company of peer learners, the accents of whom are no better. This fosters a sense of social proof, subconsciously leading the student to accept this way of speaking the foreign language. Furthermore, if the student receives passing grades in said class, they can only gather that they are doing a good job. To make things worse, there is a likelihood that the teacher is also American, having studied along this same path and received a college degree, yet never having mastered the correct accent and pronunciation, thus perpetuating this verbal folly. If a student finds himself in a classroom in which the instructor is a native speaker, and focuses on correct accent and pronunciation, he may consider himself luckier than most. However, being introduced to the written language in the beginning will serve to be an immense obstacle.

This approach results in little to no comprehension of the language when spoken by natives, little to no verbal fluency, and a noticeable or even heavy accent. Although the student may become proficient in reading and writing, the lack of focus on listening and speaking leads to the common proclamation, “I can read it better than I can speak it.”

There are some students/graduates who realize the need to be immersed in a culture in order to master a language, who later on work hard and become interpreters. However, if they fail to lose their American accent, they may face the aforementioned obstacles.

For the interpreter whose native language is the same as the LEP, different issues exist. In the United States, he majority of judges, jurors, and attorneys speak English as a first language. Therefore, when listening to the interpreted testimony of a LEP spoken with a moderate to heavy accent, often uttered without the natural intonation that a native speaker of English would use, the listener could misperceive the meaning of the message.. Also, if the Interpreter’s accent is distracting to the listener, certain nuances of the message could be missed. If the interpreter does not sound like an American when interpreting a message spoken by the LEP, the listener has to judge for himself how the message was intended to be understood. This can force the listener to mentally interpret non-native sounding English into natural sounding English.

Fortunately, there are ways to improve one’s accent and pronunciation. In the words of one of my esteemed colleagues, Ron Vásquez, “It’s all about paying attention.” Language is something that we initially learn by mimicking native speakers. The good news is that there are native speakers all around us. Any mentally and physically healthy person can learn to produce new sounds. After all, we all share similar anatomy witch respect to speech organs. If you want to improve your accent, I suggest finding a coach, preferably a native speaker.

If your pride stops you from asking for help, there is an unlimited supply of audio or video recordings that you can use to shadow and/or mimic. Start by recording yourself speaking some basic words and phrases in your foreign language. Be honest with yourself. Listen objectively and intently. Ask yourself, “Do I sound like a native speaker?” Tune in your ear to the sounds that most obviously need attention, and work on those. Watch native speakers’ mouths when they are speaking. Recreate the experiences that you had as a child when you mimicked your parents.

For those interpreters who dismiss this notion altogether, I urge you to find it within yourself to strive for ever-increasing excellency in your language profession. You and the people you serve deserve nothing less.

Resources

For those interested in improving their accent and pronunciation, I would recommend language applications such as Memrise, or Mango. They have built in features that allow you to record your voice and compare it to that of a native speaker.

[Jeff Martin is a North Carolina master certified Spanish court interpreter. He became fluent in Spanish by learning from migrant coworkers at his first full time job at a turkey plant. After working several bilingual jobs, he decided to pursue court interpreting. He became certified in 2009, and master certified in 2017. He is now focused on becoming state certified in Portuguese, as well as federally certified in Spanish.]

The views and opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official position of NAJIT.

Sole Proprietorships: Getting Ready for Tax Season

By Arianna M. Aguilar

Tax season is quickly approaching, and as small business owners, it’s time to get everything in order.

Depending on your business structure, there are forms that need to be filled out and records to be kept and produced. This article will cover taxes for sole proprietorships.

The following are some tips for getting everything ready for this year’s tax returns.

If you are a sole proprietorship, you need to make sure you have all of your accounting up-to-date, including all of your expenses and income.

For tax purposes, the IRS makes no legal distinction between sole proprietors and owners and has placed them in the same category. Though being a sole proprietor has some benefits, it does require careful accounting. As a sole proprietor, you must separate business expenses and income from personal expenses and income. Therefore, maintaining separate bank accounts for each is recommended. You may also choose to have a Doing Business As (DBA) name and bank account to facilitate the separation of personal and business income and expenses.

Sole proprietorships can deduct the following expenses: home office deductions, business expenses (as long as they are ordinary and necessary), health insurance, travel, and half of the Self Employment Tax.

Home Office Deduction

With regard to home office deductions, a portion of the space in your home can be deducted as an office space. To qualify, it must be specifically dedicated to the conduct of business and a place to meet with clients or customers. It must be for business use only. Therefore, if you work at your dining room table, you may not deduct the expenses associated with that space. To properly calculate office space deductions, you must calculate the percentage of the square footage of the home that is used as an office space. will determine the portion of your rent, mortgage payments, utilities, and other expenses that is deductible.

Some business owners are afraid to take the home office deduction for fear of being audited. However, if you qualify for that deduction, don’t be afraid to take it, as long as the space is dedicated to business use only.

Business Expenses

IRS Form Schedule C (which will be submitted to the IRS by the sole proprietor) lists the categories of business expenses. They include advertising, car and truck expenses, commissions and fees, contract labor, depletion, depreciation and section 179 deduction, employee benefit programs, insurance (other than health), interest, legal and professional services, office expense, pension and profit-sharing plans, rent or lease, repairs and maintenance, supplies, taxes and licenses, travel, meals and entertainment, utilities, wages (less employment credits).

Health Insurance Deduction

According to Turbotax, “If you are self-employed, you may be eligible to deduct premiums that you pay for medical, dental and qualifying long-term insurance coverage for yourself, your spouse, and your dependents. This health insurance write off is entered on page 1 of Form 1040, which means you benefit whether or not you itemize your deductions.”

If you are a sole proprietorship and you pay to provide health coverage for your employees, you can deduct those premiums on line 14 of Schedule C (Profit or Loss from Business).

Travel

As a sole proprietorship, you can deduct automobile expenses related to business travel. However, if you rent an office and must drive there every day when you need to work, you can’t deduct that travel because it is considered to be “commuting.” You can deduct your travel expenses if you are meeting with a client, going to the post office or the bank, or attending an industry event, among other things.

There are two ways to deduct automobile expenses. You may take a standard mileage deduction (.535 cents per mile for 2017). This covers all the general operating expenses such as gas, oil changes, repairs, maintenance, insurance, and original cost of vehicle.

The other way to deduct automobile expenses is to deduct the percentage of the maintenance, gas and insurance that is related to business use.

Now, if you have to travel overnight, you can deduct the cost of transportation (including plane or train ticket, ground transportation to the airport or train station, airport parking). You can also deduct the cost of lodging and meals.

Or, according to the IRS, “instead of keeping records of your meal expenses and deducting the actual cost, you can generally use a standard meal allowance, which varies depending on where you travel. The deduction for business meals is generally limited to 50% of the unreimbursed cost.”

Remember to keep meticulous records for mileage and travel.

Self-employment Tax

As a sole proprietorship, you have to pay self-employment tax, in addition to regular income tax. When you are employed by a company, the employer pays half of the Social Security and Medicare taxes, and you pay the other half. Therefore, that means that a sole proprietor has to pay both the employer and employee taxes. However, the sole proprietor can take a deduction for half of the self-employment taxes.

Income

Keep records of all income you receive, whether it is paid to you in cash, or by check or credit card. Even if you do not receive a 1099, you must report the income received. If you do receive a 1099, you should attach it to your return.

Preparation of Tax Returns

As a sole proprietor, you may find that you can file your own tax returns without an accountant’s help. The form that will be filled out is Schedule C and Form 1040.

Keep records of all income you receive, whether it is paid to you in cash, or by check or credit card.

However, many sole proprietors decide to use an accountant to prepare their returns accurately.

You can help out your accountant by keeping good records. Some keep receipts of expenses in an envelope and simply hand it over to the accountant at the end of the year. However, paying an accountant to reconstruct your records can be painstaking and expensive.

If you keep up with the recordkeeping on a routine basis, it will make your life easier at the end of the year. Many also find it useful to use an accounting software such as Quickbooks, and find it easiest to enter income and expenses on a daily, weekly or monthly basis.

If you use accounting software, make sure you reconcile all of your bank accounts. Check your ledger at the end of the year for accuracy in the profit and loss statement that the accounting software will produce.

Taxes do not have to be daunting for sole proprietorships. If sole proprietors keep good records on expenses and income, tax preparation will be easier in the weeks and months before April 15th.

[Arianna M. Aguilar has been interpreting and translating since 1999. She is a North Carolina master certified Spanish court interpreter and a Certified Medical-Spanish interpreter.]

The views and opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official position of NAJIT.

Those pesky CEUs: Are they really necessary?

By Agustín de la Mora

Many states have a process for interpreters to renew their certification once it is received, usually once every two years. Each state has its own process, some more involved than others, but it always revolves around providing documentation of continuing education activities, often in the form of CEUs (continuing education units). Often, this is perceived as an annoyance, complying with bureaucracy in way that doesn’t benefit interpreters at all and just making them jump through hoops.

Personally, I feel nothing could be further from the truth. I strongly believe continuing education is the key to a long, successful career in interpreting. Imagine this scenario: you visit the doctor’s office, and the doctor proudly tells you that in the 25 years since they received their medical license, they have not attended a single AMA conference! They go on to affirm they have not studied any new procedures that have been developed in the last quarter-century. They haven’t learned about new pharmaceuticals or new treatments, new guidelines or potentially dangerous reactions to medications that have been discovered. Obviously this an extreme and hypothetical example, but it serves to illustrate the point clearly. A successful interpreter is mindful of the fact that state certification indicates that they have achieved the minimum requirements to interpret accurately in court, not that they have nothing left to learn.

Just like the doctor who is just leaving medical school still has a lot to learn before being considered an expert in their field, so do interpreters have a long journey after becoming certified in order to be the best they can be.

Instead of being perceived as a chore or an inconvenience, the process of getting CEUs should be treated as an opportunity to unlock one’s passions and explore new aspects of one’s career.

Instead of being perceived as a chore or an inconvenience, the process of getting CEUs should be treated as an opportunity to unlock one’s passions and explore new aspects of one’s career. While requirements vary from state to state, most states allow interpreters to earn CEUs on a wide variety of topics, not just the mechanics of interpreting itself. Courtroom protocol, specific types of legal proceedings, ethics, and interpreting for expert witnesses are just some examples of continuing education activities that fulfill CEU requirements while allowing interpreters to go deeper and expand their knowledge of their chose profession. Find continuing education topics that address your weaknesses, solidify your strengths, and satisfy your curiosity. Instead of asking: “Do I really have to?”, maybe we can ask: “Where will continuing education take me this time?”

[Agustín Servín de la Mora is the President of the Florida Institute of Interpretation and Translation. He has been a professional interpreter for the last 22 years, both as a freelance and staff interpreter. Mr. de la Mora is a Supervisor Rater for the National Center for State Courts and has been a Lead Rater for the federal and consortium oral exams for court interpreters. He was the Lead Interpreter for the Ninth Judicial Circuit for over a decade, is a member of the Florida Court Interpreter Certification Board and a voting member of the Technical Committee of the National Consortium for Interpreter Certification. Mr. de la Mora is certified by the Administrative Office of the United States Courts as a Federally Certified Court Interpreter. He is also a Certified Court interpreter by the Florida Court Interpreter Certification Board and a Certified Medical Interpreter by the National Board of Certification for Medical Interpreters. He has been a consultant for the Administrative Offices of the State Courts, conducting orientation seminars and advanced skills workshops for interpreters in many states. As a recognized professional in his field, he has been featured as a speaker and presenter in several national conventions, including the National Association of Judiciary Interpreters and Translators, the American Translators Association and the National Association of State Court Administrators.]

The views and opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official position of NAJIT.

NAJIT News

Letter From the Chair

Letter from the Chair: Proteus 2017/18 Winter Volume XXX Issue No 2

By Gladys Matthews, Ph.D.

Dear colleagues,

2017 was an exciting year for NAJIT, and 2018 is shaping up to be even better. In 2017, we received the largest number of submissions for annual meeting presentations in NAJIT’s history, but I’m excited to tell you that we have received even more submissions for the 2018 conference in San Francisco. Hilda Shymanik and all the members of the Conference Committee are already hard at work putting together a conference program packed with great sessions. As always, there will be how-tos to help all of us become better interpreters, translators, linguists or better at working with them, as well as expert presentations on the key issues facing our profession. This year, we are making a special effort to include sessions for interpreters and translators working in a wide range of languages. Also, in keeping with NAJIT’s tagline – Empowering Interpreters and Translators WorldwideTM – we hope to expand international participation in the conference. I believe the 2018 annual conference will be the best yet, and it’s not too soon for you to make plans to attend.

The NAJIT committees are all up and running and their work will be in full swing after the holidays. As I have said before, we can only make a difference by organizing and maintaining consistent efforts to advance our profession, which are made through our committees. I want to express my appreciation to the chairs and to everyone who volunteered to serve on one of NAJIT’s committees.

Thanks to the efforts of Cecilia Golumbeanu, Andre Moscowitz, Kathleen Shelly, and Rosemary Dann, NAJIT’s newsletter keeps everyone informed about the work of our association and key developments in the profession. The NAJIT listserv, moderated by Cristina Courtright and Bethany Korp-Edwards, continues to fill a real need. I would like to invite you all to contribute ideas and articles to our Newsletter and participate actively in discussions on the listserv.

Membership continues to grow, but all of us on the Board of Directors believe we can grow NAJIT even more. We are taking steps to increase our outreach to prospective members and are committed to delivering high-quality products and services that demonstrate the value of NAJIT membership (like the members-only job board on the NAJIT website). We want an even larger proportion of interpreters and translators to join with us to strengthen our profession as it grows in importance to the nation. Please encourage all your colleagues and fellow interpreters to join us!

I want to take advantage of this opportunity to express a heartfelt thanks to my fellow board members, Aimee Benavides, Ernest Niño-Murcia, Julie Sellers, and Hilda Shymanik, as well as Rob and Susan Cruz of our management company, for all their hard work on behalf of NAJIT. Thanks are also due to Arianna Aguilar, Editor-in-Chief of Proteus, to all the members of the Proteus committee, and to the all the authors for this great issue and their work throughout the year.

Sincerely,

Gladys Matthews

Chair, NAJIT

Taking the Hill: NAJIT’s Advocacy Day in Washington D.C.

By Zeng Zeng Yang

“We are our own worst enemies. I have been to so many conferences at which my colleagues complain about the low pay, the cutthroat competition, problems with the courts, and yet few take any concrete action to reach out to decision-makers,” said Dr. Liu, the president of the International Federation of Translators (FIT), who was the keynote speaker of the NAJIT 38th Annual Conference held near Washington, DC, on May 19-21, 2017. FIT, which NAJIT has recently joined, is the voice of professional associations of translators, interpreters and terminologists around the world.

Going to the Capitol

Well, this time some NAJIT members took action. On May 22, 2017, the day after the conference, a small group went to the Capitol and lobbied their legislators to promote professionalism and professional standards, to advocate for a judicial system that functions for all and to campaign for a better future for our profession and its practitioners.

We came from different states—California, Indiana, Nevada, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania and Washington—and represented several languages other than English: French, Korean, Mandarin Chinese, Nepali, Russian, Spanish and Tibetan. Dr. Liu, from New Zealand, and Samantha Cayron, a researcher at the Centre for Legal and Institutional Translation Studies in Switzerland, came along to support NAJIT’s advocacy efforts.

Well, this time some NAJIT members took action.

“In Switzerland, the government has a very democratic way of dealing with issues and the citizenry is very involved in the defense of their rights. Having lived in Mexico and France, I think systems only work when people actually use and believe in them,” said Dr. Samantha Cayron.

From the conference hotel, we took the metro to the Capitol. Upon arrival, the team split into two groups. One group proceeded to attend pre-scheduled appointments with legislative staff, while the other visited different offices without appointments. In all cases, they succeeded in talking to legislators’ aides.

Use of credentialed interpreters and translators

NAJIT’s advocacy priority number one is to convince the government and the public at large to always use credentialed interpreters and translators. “We routinely provide language access services to the court, making sure that we send interpreters certified or registered by the court. Every year, however, there are always three or four new languages for which we need to find competent interpreters,” said Emma Garkavi, Seattle Municipal Court Language Access Coordinator. “There is a need for US federal courts to create court interpreter certification in many more languages than just Spanish.” The other alternative is to contract with state certified and registered court interpreters, which federal courts don’t always do.

Difference between registered and certified interpreters

The National Center for State Courts (NCSC) has developed written and oral exams for legal interpreting. State court interpreters have taken mandatory orientation and training, passed the NCSC written exam, gone through a criminal background check and have sworn an oath to abide by a legislated code of professional conduct. In addition, they are subject to disciplinary action and must comply with continuing education to maintain their credentials. Certified court interpreters have passed the NCSC oral exam, which tests their interpreting skills in the simultaneous, consecutive and sight translation modes. Registered court interpreters have had passed oral language proficiency exams in English and the other language, but have not yet passed the certification exam.

“In the private sector,” said Ms. Garkavi, “companies such as Microsoft or Starbucks specifically request state certified court interpreters. They know these interpreters have had their skills tested in all three modes of interpreting: simultaneous, consecutive and sight translation. In contrast, the Executive Office of Immigration Review has a contract with a nationwide vendor allowing non-certified or registered court interpreters with one year of experience to work in immigration courts. These unqualified interpreters can potentially cause immigrants to lose their rights or to allow potentially dangerous people to stay in the country.”

“In the ,” said Ms. Garkavi, “companies such as Microsoft or Starbucks specifically request state certified court interpreters. They know these interpreters have had their skills tested in all three modes of interpreting: simultaneous, consecutive and sight translation. In contrast, the Executive Office of Immigration Review has a contract with a nationwide vendor allowing non-certified or registered court interpreters with one year of experience to work in immigration courts. These unqualified interpreters can potentially cause immigrants to lose their rights or to allow potentially dangerous people to stay in the country.”

The use of non-credential interpreters in other fields

The same issue of using non-credentialed interpreters applies to many other fields. In public schools, for example, failing to use credentialed interpreters sometimes means that limited English proficient parents can misunderstand the details of the individual education plans designed to benefit their children, rendering them unable to help their children succeed in school. In healthcare, meaningful language access is frequently not provided meaningful to patients, which can result in uninformed consent. “In Ohio, trained and qualified Nepali interpreters have shared that dozens of babies from Nepali speaking parents were circumcised without their parents understanding what was happening because healthcare providers were using untrained and unqualified interpreters. Circumcision is not in their Hindu or Buddhist tradition. This creates mistrust in immigrant communities,” informed Adriana Fonseca, a state court certified interpreter and member of the group that visited the Ohio office.

“The working conditions and pay for medical interpreters needs to increase,” said Milena Calderari-Waldron. “Their services are so critical, yet they get paid so little.”

One way to make this happen is to streamline procurement and improve scheduling efficiencies. “For traffic violations, the court can schedule all infractions for a specific language on the same day. One court does it on Tuesday morning and another court on Tuesday afternoon. In this way, we can pay interpreters better and use the limited pool of certified and registered court interpreters more efficiently. In healthcare, staggering appointments every 45 minutes for the same language results in one single interpreter taking care of multiple patients in one location. Interpreters travel less and earn more,” explained Emma Garkavi.

Inadequacy of labor categories

The origin of some of these problems is the inadequate labor categories found in the SCA Directory of Occupations published by the US Department of Labor and used to make wage determinations. The Service Contract Act (SCA) applies to every contract entered into by the United States Government. It requires contractors and subcontractors performing services on prime contracts in excess of $2,500 to pay service employees no less than the wage rates and fringe benefits found prevailing in the locality (e.g. state, county or city) or in a predecessor contractor’s union contract.

“The US Department of Labor has commingled interpreters with translators. NAJIT spearheaded the creation of much more accurate descriptions of who we are, what we do, and how we do it,” said Milena Calderari-Waldron, a Spanish court interpreter who is also certified by the Washington State Department of Social and Health Services Medical and Social Services and organizer of the trip to the capital.

Another problem is that the Bureau of Labor Statistics is under the impression that interpreters and translators are for the most part employees. Its website states that 1 in 5 were self-employed in 2014. In contrast, the American Translators Association’s 2016 Translation and Interpreting Services Survey found that 76% of interpreters and translators are freelancers, which is corroborated by the Association of Language Companies’ 2015 Industry Survey, which found that 89% of language services are rendered by freelancers.

Additionally, and contrary to current laws and regulations, the US Government is ignoring voluntary consensus professional standards such as those created by the American Society for Testing and Materials and the International Standards Organization when it procures language services. “Government agencies are writing their requests for proposals based on inaccurate information. There is a complete disconnect between them and us, the professionals actually performing the service,” said Milena Calderari-Waldron echoing what Dr. Liu had said in his keynote speech. There is much to advocate for, indeed!

Our voices need to be heard. After all, when it comes to interpreting and translation we are the experts. “Legislators are always interested in hearing from their constituents,” said Helen Eby who has successfully lobbied Oregon’s legislature and executive branch agencies for years. She insists that members should take the action to their home states. “Speak out for your profession; talk to your senators and representatives in your state; and talk about the issues.”

As a student, that day I learned a lot about the current debate raging in our profession. It was such an eye-opening experience to walk through those Capitol buildings and see these colleagues voicing their concerns to their legislators with strong evidence and concrete solutions. In fact, I learned just as much about the current state of this profession during Advocacy Day as I did during the conference.

For more information:

To learn about what advocacy is, its importance, and how to advocate for our profession, please read “Advocacy 101 for Interpreters and Translators”, a resource prepared by the NAJIT Advocacy Committee.

Zeng Zeng Yang is a published author in China and the former co-editor of her high school newspaper. As a high schooler, she interned for her State Senator. She is an incoming junior at Moravian College, where she is pursuing a degree in mathematics with a minor in philosophy. She is currently working on becoming a certified court interpreter in English<>Mandarin for the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

The views and opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official position of NAJIT.

NAJIT 39th Annual Conference

Regular Columns

For Better or Verse – Thoughts While on a Dreary Drive

By Hal Sillers

Thoughts While on a Dreary Drive

Driving through the cold drizzling rain

To an assignment where we shall gain

Green dollars received with no disdain,

And we consider coming winter’s pain.

Fear not, though the warm days wane

As ice, snow ‘n cold become the bane

Of existing here on this northern plain,

We’re buoyed to know it’s not in vain.

As is our custom, we always refrain

From any comment, do not explain.

To our profession it seems germane,

Conform to ethics and not complain.

For we surely know that we’ll retain

Lessons learned, and need not feign

Joy at navigating white, slick terrain

That may have us use crutch or cane.

Yet, here in this place we still remain

In hope that we shall someday attain

Life full of much less stress and strain,

And retire with luck to warmer Spain.

[Hal Sillers is a MN State and federally certified interpreter of Spanish and frequent contributor to this column. Hal is also the Staff Interpreter for the MN 8th Judicial District.]

Items of Interest

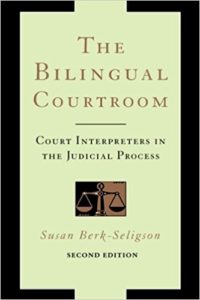

Book Review: The Bilingual Courtroom – Court Interpreters in the Judicial Process

The Bilingual Courtroom – Court Interpreters in the Judicial Process, 2nd Edition

Author: Susan Berk-Seligson

Publisher: The University of Chicago Press, 2017

Pages: 363

By Gladys Matthews, Ph.D.

Susan Berk-Seligson’s The Bilingual Courtroom. Court Interpreters in the Judicial Process is a comprehensive empirical study of the use of interpreters in court settings in the United States and one of the most important works in the field. The first edition dates from 1990, and in 2002 a new edition was published, but curiously it was not referenced as the second edition (instead, the cover contained the tag “With a New Chapter”). Consequently, while the 2017 edition is listed as the second edition, it is in fact the third one.

This new edition reflects the extensive additions to the literature in the field of court interpreting in the past 15 years, including NAJIT’s Code of Ethics and Professional Responsibilities. As the author says, the new references highlight the recognition given to this field of inquiry. The new edition also discusses the geopolitical events that increased the need for skilled interpreters in languages other than Spanish, including the war on terrorism in the wake of the 9/11 attacks and, more recently, the immigration crisis involving thousands from the Middle East fleeing war and seeking asylum. It also discusses the growing need for qualified interpreters in languages of lesser diffusion, including indigenous languages. In some cases, relay interpreting is needed due to a shortage of interpreters who can interpret these languages directly into English.

In this edition, the author shows how the presence of an interpreter transforms court proceedings into what she calls a bilingual event; as suggested by the subject and title of the book: The Bilingual Courtroom. To understand the bilingual courtroom, she draws on seven months of ethnographic observations and 114 hours of recordings of interpreted proceedings from federal, state, and municipal courts.

The Bilingual Courtroom contains ten chapters and seven appendices. Chapter 1 gives an overview of the role of the interpreter in legal settings, Chapter 2 discusses the complex characteristics of legal language, and Chapter 3 reviews the legislation, court opinions, and executive orders that guarantee the right to an interpreter. Chapter 4 describes the methodology used in the study, including the collection of thousands of hours of recorded court proceedings and transcription of the 114 hours selected for analysis. Researchers and others will be interested in her discussion of the challenges that obtaining permission from all parties involved (attorneys, judges, defendants, etc.) entailed. These transcriptions are used in Chapter 5 to illustrate the way the interpreter sees her role and is seen by other participants in the courtroom, as illustrated by such events as departures from court protocol by judges and attorneys who address the interpreter rather than the witness or defendant and attempts by the interpreter to clarify the utterances of various parties, including attorneys’ questions, witness’s answers, etc.

Chapter 6 and 7 draw from the data and evidence to show the range of ways interpreters use language to affect what happens in the courtroom, including use of the passive and active voice and other pragmatic elements that have subtle – or not so subtle – effects on the rendition. As one example, the consequences of interpreter approach to pragmatic elements may include making the tone of the attorney or witness harsher than intended or, conversely, softer and more cooperative than the original. This fascinating analysis suggests that interpreters are far from passive or neutral mouthpieces in the courtroom, but must be thought of as active participants in the judicial process and proceedings. Chapters 8 and 9 analyze the consequences of these “alterations” and suggests that they have significant impact on the outcomes of judicial proceedings. Some of this analysis is based on interviews with jurors in mock trials, and suggests that the interpreter’s approaches can shift juror views of witness trustworthiness, competence, and other traits. The author also cites evidence that alleged shortcomings in the quality of interpretation is increasingly being cited as grounds for appeal.

Chapter 10 concludes the book by covering recent developments in the field, including quasi-judicial settings such as immigration court (including asylum cases), police settings, and jails and prisons. The chapter also summarizes a number of recent studies in which analysis of pragmatic elements of interpreted courtroom language has revealed shifts in meaning that likely have a significant impact on the results of court proceedings (an analysis of the effect of interpretation on leading questions is particularly interesting).

This brings us to the essential question this book review needs to answer: Is this a book that legal interpreters, and those who train, employ, or interact with them, should read? The answer is yes for several reasons, First, Berk-Seligson conveys the unequivocal message that interpreting is highly demanding intellectual task and that skilled interpreters should be held in the highest regard. More importantly, she documents with extensive research the fact that how well interpreters do their jobs makes a real difference in the outcomes of judicial proceedings. That is something that everyone involved in the judicial process – particularly interpreters – need to understand.

For interpreters, however, the value of The Bilingual Courtroom goes beyond documenting the importance of interpreters and effective interpretation. The Bilingual Courtroom is one of the few books that analyzes deviation of meaning in the rendition when the interpreter does not consider pragmatic aspects of language such as context, communicative style, and implied meaning. The book is full of concrete examples, derived from research, of the specific pitfalls that can befall interpreters. Interpreters usually view vocabulary as their main linguistic challenge, but Berk-Seligson argues that this results in inattention to politeness, length of answers, passive voice, formality, and other pragmatic aspects of language which may result in distorting the intended meaning. She clarifies that these distortions are for the most part made unconsciously, which is all the more reason for interpreters to be aware of them and understand how to address them.

By drawing on the extensive literature of pragmatics and discourse analysis, the book offers considerable insights into where and how interpreters can focus their own self-assessment and self-improvement efforts – as all interpreters understand, a never-ending process. While her study is based on court proceedings in English and Spanish, the approach can be applied to other languages. In particular, the book is essential reading for researchers and trainers of interpreters, as well as for any interpreter who wishes to better understand their role in the judicial system and the context for their work. Indeed, the book is recommended by the National Center for State Courts for those preparing for state certification exams. The 2017 edition makes an excellent book even stronger, and The Bilingual Courtroom should find a place on the bookshelf of serious court interpreters.

[Gladys Matthews holds a degree in French from the Universidad de Costa Rica, a Master’s degree in terminology and translation and a Ph.D. in linguistics with an emphasis in legal translation from Université Laval in Canada. She has extensive experience as an English/French into Spanish translator, specializing in legal and education policy translation. An experienced court interpreter, Matthews trained at the Agnes Haury Institute of the University of Arizona and is certified in the state of Indiana. She is currently Course Director and court interpreting courses coordinator in the Master of Conference Interpreting of Glendon College of York University, Toronto. She developed two court interpreting courses for the program –one taught in English and the other in English-French– and has been teaching them on-line for over five years. She also served as program director and faculty member in various colleges and universities, including Metropolitan State University of Denver, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, and the College of Charleston. She has trained and worked as a medical interpreter and is a registered family law mediator in Indiana.]

The views and opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official position of NAJIT.

Book Review: Manual de traducción jurada de documentos notariales en materia de sucesiones entre los sistemas jurídicos francés y español: La Traductología Jurídica aplicada a la práctica

Manual de traducción jurada de documentos notariales en materia de sucesiones entre los sistemas jurídicos francés y español: La Traductología Jurídica aplicada a la práctica

Author: Samantha Cayron

Publisher: Editorial Comares (Granada, Spain), 2017

Language of publication: Spanish

Pages: 368

Features: examples of notarial deeds; comparative charts; diagrams; color-coded charts

By Julie Sellers, Ph.D., FCCI

Abstract: Samantha Cayron’s Manual de traducción jurada de documentos notariales en materia de sucesiones entre los sistemas jurídicos francés y español: La Traductología Jurídica aplicada a la práctica offers a comparative study of the translation of notarial deeds of succession drafted in the Spanish and French legal systems. The author includes examples in those two countries’ legal systems to illustrate this approach and to provide a framework for applying the same techniques to other texts and language pairs.

Samantha Cayron’s 2017 publication, Manual de traducción jurada de documentos notariales en materia de sucesiones entre los sistemas jurídicos francés y español: La Traductología Jurídica aplicada a la práctica (Handbook of Legal Translation of Notarial Deeds of Succession in the French and Spanish Legal Systems: Legal Translation Studies Applied to Practice) provides an in-depth study of notarial deeds drafted in the legal systems of Spain and France. The author applies a comparative approach based on functionalist theory within the broader context of legal translation, and more specifically, in the specialized context of notarial deeds of succession. This method allows her to highlight the role of the translator as mediator, not only between languages, but between cultures, contexts, and legal systems. This pragmatic approach allows translators of these types of deeds to produce a target text that is equivalent in function to the source text. Cayron includes concrete examples culled from actual sources from both the French and Spanish legal systems to illustrate the benefits and limitations of the comparative approach and to provide a framework for applying the same techniques to other texts. Although highly specific to content (notarial deeds of succession) and context (the French and Spanish legal systems), this manual offers several techniques that are applicable to other contexts and language pairs.[1]

Cayron’s Manual is her doctoral dissertation, and the structure of the book corresponds to the common structure of such studies. The author begins with a review of the literature, an explanation of her theoretical approach, and a description of her research method. She explains in detail the various types of deeds that comprise the greater corpus of notarial deeds in the legal systems of France and Spain, as well as her selection process for the documents included in her study. Cayron also specifies the measures she has taken to assure the confidentiality of those individuals whose notarial deeds serve as examples in her study.

Contextualization

From this theoretical and methodological foundation, Cayron proceeds to provide the judicial context for Spain, France, and her native Mexico, since she does include a selection of documents from that Latin American country. This contextualization is essential to a true and accurate translation. The comparative charts in this section are useful in illustrating the parallels between the laws of France, Spain, and Mexico City the author illustrates the importance of situating a text within its legal context both in the source and target languages with an example of the subtle differences between terms related to heirs apparent and legatees in the French and Spanish legal systems. She also explores inheritance laws and the regulations that frame the notary’s work in the countries of study, along with the general process and documents involved in questions of succession.

Cayron dedicates a chapter to an in-depth exploration of the public instrument, highlighting aspects pertinent to the translation of notarial deeds of succession. She outlines the particular elements of style, formatting, and language of these deeds, along with other unique features, such as the type of paper used, official seal, signature, and numbering system. She also identifies their various conventions through sample texts, illustrating and expanding upon them in the body of the chapter.

The Translation Process

The fourth chapter presents the primary focus of the book in which Cayron applies her theory and method to the translation of a notarial deed (French to Spanish). This lengthy chapter traces the translation process, providing side-by-side charts to present excerpts of the source text and its corresponding translation, along with in-depth comments that underscore the author’s decision-making process during the translation. As part of this process, the author compares inheritance laws from the target language system with that of the source, highlighting them with different colors of ink. This visual presentation is particularly useful in identifying similarities. As the author notes, this type of comparative analysis allows the translator to generate a substantial portion of the target text by studying the existing laws. This approach is applicable to other language pairs and legal contexts.

Cayron’s Manual is highly specific both in its language pair and its treatment of notarial deeds of succession. Readers must have a fairly sophisticated reading knowledge of Spanish to understand the text; Spanish translations of French terms are included. Despite these drawbacks, the study is based on sound theory and methodology, and it includes multiple examples in a single text. Her comparative approach to studying inheritance laws in the source and target language systems is applicable to other areas of legal translation. Cayron’s study is recommended for legal translators of deeds of succession, or to serve as a roadmap for translating other legal documents.

[1] Although this book is written in Spanish with numerous references to French translations, the author of this book review has intentionally refrained from including specific terms in Spanish and/or French in an effort to reach Proteus’s diverse audience who work in a variety of language pairs.

[Dr. Julie A. Sellers, a specialist in adult second-language acquisition and in Latin American popular culture and identity, is an Associate Professor of World and Classical Languages and Cultures (Spanish) at Benedictine College, in Atchison, Kansas, and she is a federally certified court interpreter (English<>Spanish). Dr. Sellers has published on language acquisition and interpreting skills and advocacy in a variety of publications, such as The Language Educator, Proteus, and The Wyoming Lawyer. She published her third book, The Modern Bachateros: 27 Interviews in 2017 (McFarland).]

The views and opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official position of NAJIT.