While I crank out dozens of emails, texts and Facebook posts a day, I haven’t actually written a letter in over two decades, so this feels a bit daunting. But here it goes…

Proteus

Issue: 2016/17 Winter Volume XXVIV Issue No 3Table of Contents

Editor's Corner

Letter from the Editor

Those of us from the Proteus staff are very excited about our new format—thanks to the tireless efforts of Executive Director Rob Cruz and his team. We hope you enjoy it as much as we do! We are also very excited about this issue’s feature articles: a special report on immigration court, a discussion of a controversial jury instruction in California that asks jurors to notify a judge when they believe the court interpreter has made an error, and a review of Javier F. Becerra’s new online English-Spanish legal dictionary. These, along with our regular columns, should provide you plenty of food for thought, and hopefully some enjoyment, too.

And yet there’s so much more we could publish! How about a column on interpreting and technology? Perhaps a review of a simultaneous interpreting app? An article on how video remote interpreting is used in your area? The new contractor promising improved working conditions for U.K. court interpreters, or Afghan interpreters waiting for a visa?

These are just some of the issues we would like to shed some light on. Of course, there are many, many others. It’s very easy for us interpreters to get caught up in our own geography as we focus almost exclusively on the issues we are currently facing in our respective regions, and in our own courts, whether federal, state or immigration, at the expense of checking up on our colleagues from other corners of the U.S., or the world for that matter.

We invite you to submit an article from your corner of the interpreting community. We are eager to hear about the problems you are encountering and, more importantly, your solutions. Each of us is adapting to tight budgets and technological innovations the best we can. Our hope is that a publication such as Proteus can help us do so even better.

With kind regards,

Dan DeCoursey, Proteus Editor-in-Chief

Meet the Editors

Arianna M. Aguilar has a degree in communications and has been interpreting and translating since 1999. She has been a certified court interpreter in North Carolina since 2005, and master certified Spanish-language court interpreter since 2013. She is president of Latino Outreach Consulting of NC, Inc., a translation and consulting agency, and is a published author. She has given presentations on a range of topics at both NAJIT and American Translators Association (ATA) conferences.

Rosemary Dann currently lives in Phoenix, AZ. (Yes, but it’s a DRY heat.) She holds a B.A. and M.A. in Spanish language and literature, as well as a J.D. degree. She is also a Massachusetts state-certified Spanish-language court interpreter. She has worked as a high school and college instructor, held various law jobs including law clerk to two judges, a public defender, and a private practitioner, and has free-lanced as a judiciary interpreter in Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Florida. She joined NAJIT after attending “The Institute” in 1999 (thank you, Cristina Helmerichs!) and has since served on numerous NAJIT committees and on the Board of Directors for six years, two as chair. She took over the position of editor-in-chief of Proteus upon Nancy Festinger’s retirement from that post, and now turns over the reins to the very capable Athena Matilsky. She is staying on staff as the unofficial “advisor-in-chief”, as she has returned to college as a theater major in performing arts. Her bucket list includes visiting Machu Picchu, seeing her son married, and appearing in a national TV commercial.

Dan DeCoursey is a state and federally certified court interpreter in San Diego, as well as an ATA-certified Spanish>English translator. After working for several years as a teacher and textbook editor, he was ready to make a change, so he moved to Guadalajara, Mexico, where he earned a master’s degree in translation and interpreting from the Universidad Autónoma de Guadalajara. He has over a decade of experience working as an interpreter in both state and federal court, and as a freelance translator specializing in legal documents. Currently, he is a staff interpreter at the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of California (San Diego).

Andre Moskowitz is a Spanish-language interpreter certified by the United States federal courts and the California state courts. He is also a Hispanist, lexicographer and dialectologist, who has published a series of works in the areas of Spanish lexical dialectology and Spanish lexicography. He taught English in Colombia and Ecuador for four years, and holds a B.A. in humanities from Johns Hopkins University (1984), an M.A. in translation studies from the City (more…)

Feature Articles

It’s Finally Here! A Chat with Javier F. Becerra About His New Online Dictionary

By María Fernanda Arámbula

Yes, it is finally here! Javier F. Becerra’s English-Spanish Dictionary of United States Legal Terminology is now available online at diccionariojfbecerra.com. Why did the author decide to go online? When I asked him, Javier F. Becerra answered: “There were three main reasons: First, for practical purposes: one day I bumped into a former student of mine, Becky Serviansky, an interpreter, at the legal department of a major bank in downtown Mexico City and saw her carrying the two printed—and heavy— dictionaries; she told me that she never got to work without them. It was then that I realized how complicated it was to be carrying the two existing volumes from one place to another. Secondly, because technology is always one step ahead of us; new generations are no longer into printed books but more into IT, so I needed to keep up with the current technological advances. Last, but not least, the flexibility of an online dictionary that would allow me to make changes and corrections (in case of repeat terms, for example) and updating its content from time to time with new and interesting legal terms that had not been included in the printed version and that may prove to be useful for the readers.” These reasons can be clearly seen in the dictionary’s site map, as we will see below.

In the section “Nosotros” (“Who we are”), we find a brief introduction to what the site offers to visitors: over 22,000 terms set out in a versatile platform that not only provides definitions but also short explanations of the legal language commonly used in different areas in the United States legal system, and equivalent terms and concepts in Mexico’s legal system.

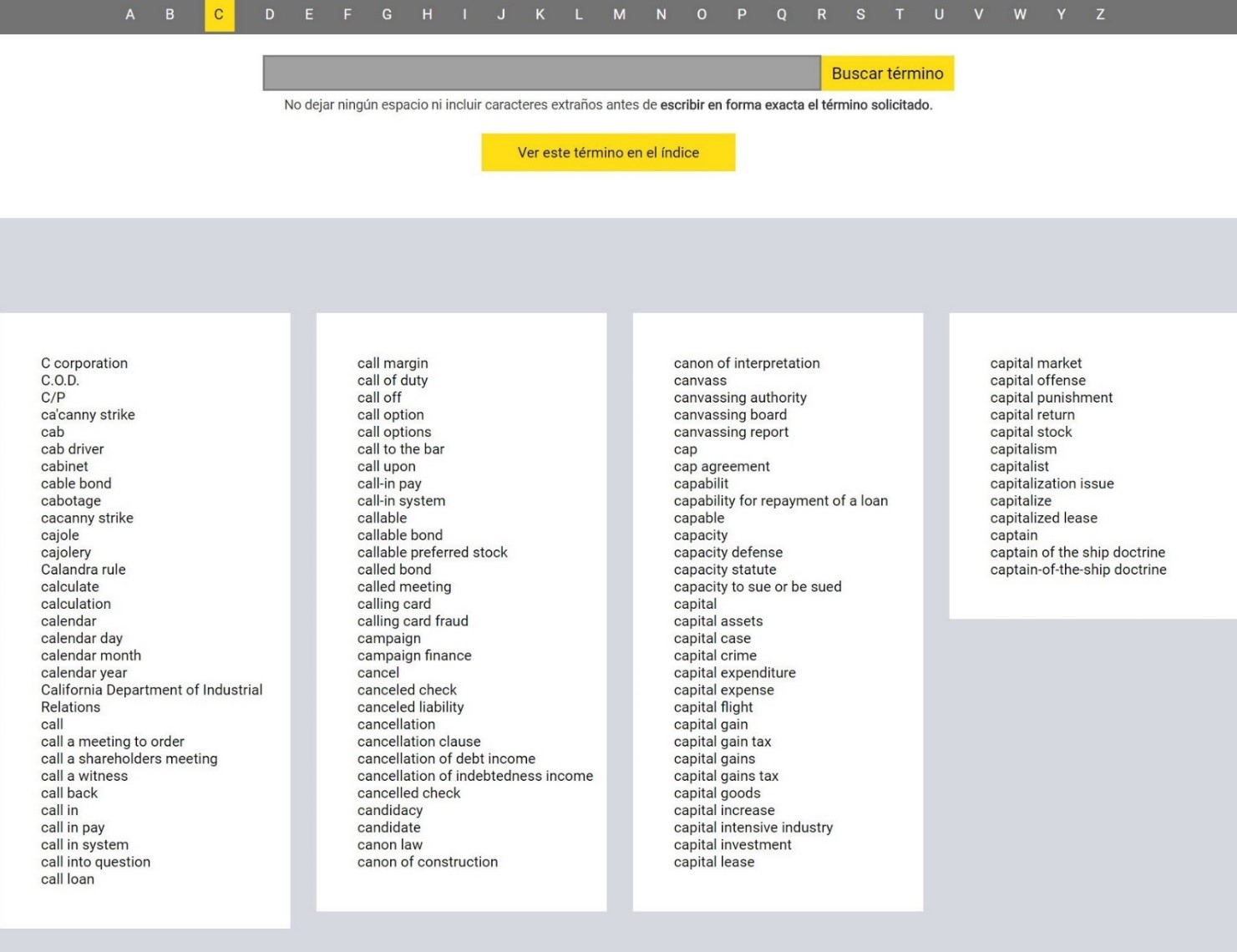

The platform is very practical and user friendly: just click on the section “Diccionario” (“Dictionary”), key the term or phrase you are searching for, and its equivalent immediately pops up.

You can also search the term through the index.

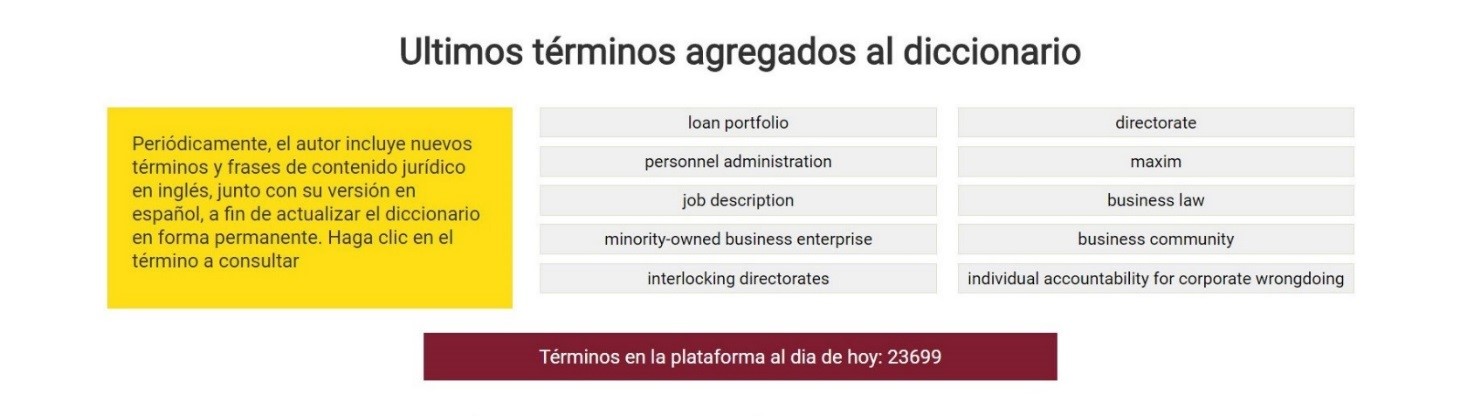

Despite the exhaustive nature of this unique work, the ever-changing nature of U.S. legal language makes this online version a very special tool. The section “Últimos Términos Agregados al Diccionario” (“Latest Terms Added to the Dictionary”) has been designed to allow Becerra to continue his research into complex legal terms and concepts that enjoy day-to-day use in the U.S., but not so in Mexico.

Becerra told me, 'I do not intend to possess the whole truth and nothing but the truth about the Mexican and the U.S. legal systems.'

Becerra told me, “I do not intend to possess the whole truth and nothing but the truth about the Mexican and the U.S. legal systems. All languages are alive and constantly evolve, and I continue to research the origin, historical background, former and current usage of terms that are not yet included in the dictionary and are uncommon to our legal tradition. Then, I put them into context, both ordinary and legal, and finally attempt to translate them into short words or phrases in Spanish, so that the end user will understand not only the translated words, but their legal meaning as well.” There is also a section on “Términos Modificados Recientemente” (“Recently Modified Terms”) to make corrections and adjustments to existing terms and phrases.

Becerra told me that “this effort has been going on as a side interest of mine and as an upshot of my tough and challenging legal practice dealing with major multinational companies and their U.S. legal counsel, ever since I started working for my law firm forty-seven years ago.” Becerra has spent all that time building up this impressive collection of terms both as a full-time bilingual attorney and also as a professor at the Escuela Libre de Derecho, a prestigious law school in Mexico City, where he has been teaching courses on legal English for more than twenty-six years now, not only to law students but also to lawyers, translators, interpreters and others interested in learning the practical aspects and complexities of the U.S. legal terminology in a workshop environment. With all that experience, the author has been able to research, contextualize, explain and translate peculiar and frequently convoluted legal terms whose meanings are extremely difficult to discern by the uninitiated, such as “cat’s paw theory of discrimination,” “grandfather clause,” “clawback agreement,” “rabbi trust,” “make-my-day statute,” “three-strikes-and-you-are-out law,” “Ponzi scheme”—only to mention a few examples.

In this new online platform, Becerra has given users a chance to interact as well. In the section “Preguntas de Usuarios” (“Questions by Users”), users are free to express their opinions tête-à-tête with the author by posing questions or stating their views on difficult legal concepts or expressions they may be dealing with, in a practically “live” two-way exchange, in fields such as family law, real estate, corporate law, contracts, labor law, financial law and assorted topics. “It is my intention to try to give an answer in two business days at the latest, except if I am travelling,” said the author.

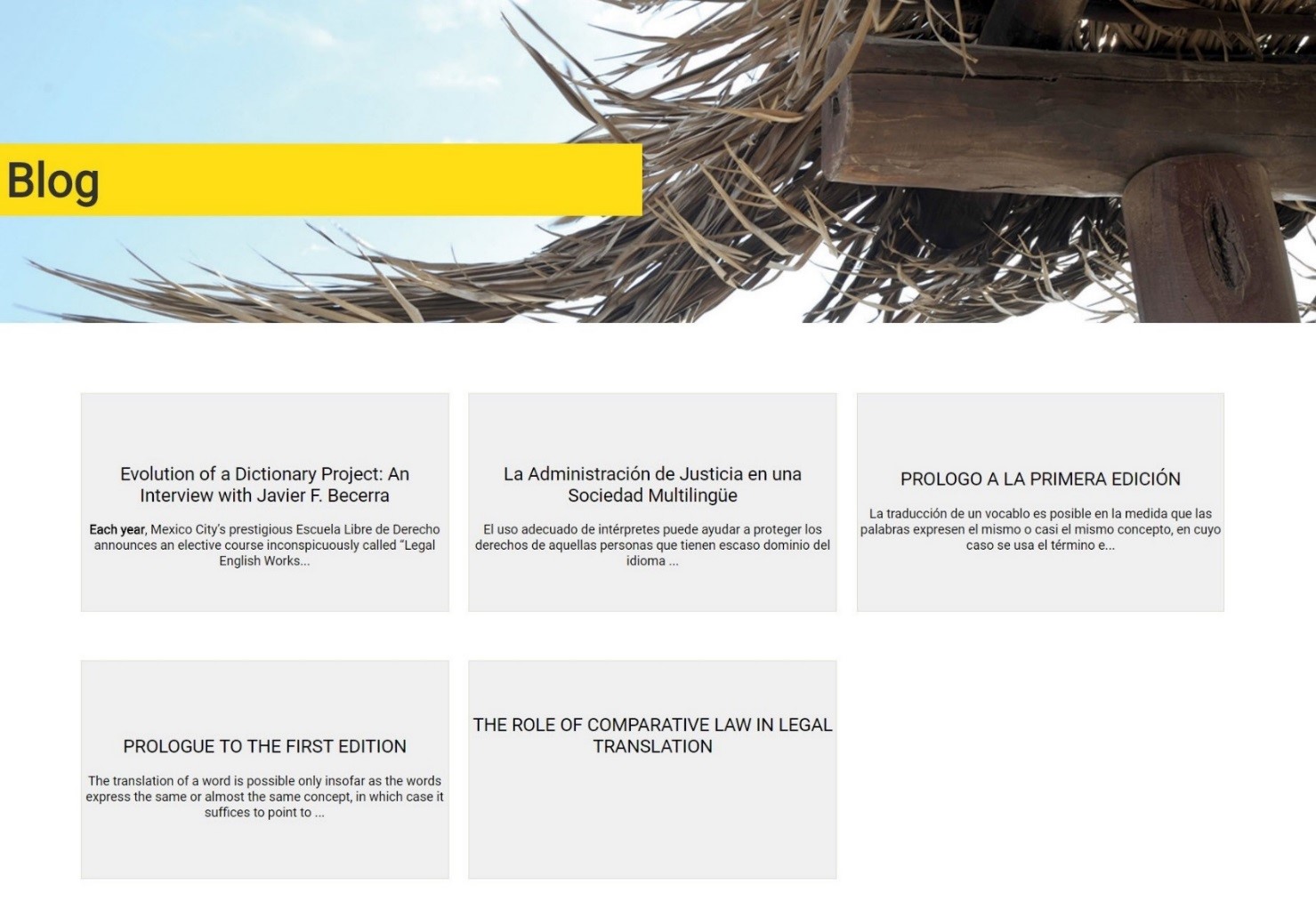

In addition, the platform contains a blog that includes different materials and documents related to the dictionary and to legal topics that may come in handy for all those users wishing to gain a deeper knowledge of certain subjects, such as the Spanish translation of an article written by Stephen M. Kahaner on the rules applicable to judicial interpreters in the U.S.

Moreover, Becerra included a section entitled “Ejercicios de Inglés Jurídico” (“Legal English Exercises”), where he offers free access to materials from his legal English workshop at the Escuela Libre de Derecho.

Subscriptions to the online dictionary may be purchased with a credit card for a $US10.00 monthly fee, US$50.00 six-month fee, or a US$90.00 annual fee. In addition, there is also a single corporate subscription for five to ten users at an annual fee of US$80.00 per user.

I believe that Becerra’s decision to offer this dictionary online was a wise one, as it will enable him to provide updated legal information, concepts and terms on a dynamic platform that allows for day-to-day communication between Becerra and dictionary users in order to keep legal language alive. When I asked him about his Spanish-English dictionary on Mexican legal terminology, Becerra stated enthusiastically: “I am already making plans to prepare the online version, but believe it will probably take two more years to upload and offer it to the public. First, I have to assess the results of the English-Spanish version [on U.S. legal terminology] before taking the other one on.” I, for one, believe the wait will be worth it.

[María Fernanda Arámbula was born in Mexico City and studied translation at the Instituto Superior de Intérpretes y Traductores. In 2000, she became part of Basham, Ringe y Correa—a prestigious international law firm, as a legal in-house translator under the lead of Javier F. Becerra. By 2007, she had become an expert translator certified by the Superior Court of Justice for the Federal District in both English and French, and in 2008 she completed her law degree at Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. She has recently concluded her master’s degree in American law at the same institution. María Fernanda has been working as an expert freelance translator for almost ten years and has been teaching legal translation in the master’s degree program at Universidad Anáhuac. She has participated as a lecturer in events such as the “Transius Conference 2015” and at the VI Congreso Latinoamericano de Traducción e Interpretación 2016 held in Buenos Aires. She is currently working on her dissertation.]

Analyzing CALCRIM 121: Are Bilingual Jurors “Triers of Fact” or “Triers of Language”?

By Joel E. Rubert, J.D.

In California’s state courts, when the court anticipates that testimony may be given in a language other than English at trial, it may read CALCRIM (California Criminal Jury Instructions for Judges and Attorneys) Instruction No.121 to the jury, either before the witness testifies or, if the instruction is modified, before the case is handed to the jury for deliberations. The instruction states:

An interpreter will provide a translation for you at the time the testimony is given. You must rely on the translation provided by the interpreter, even if you understand the language spoken by the witness. Do not retranslate any testimony for other jurors. If you believe the court interpreter translated testimony incorrectly, let me know immediately by writing a note and giving it to the (clerk/ bailiff). [Judicial Council of California Criminal Jury Instructions (2013)]

This jury instruction has prompted many court interpreters to express strong disapproval. The objections raised have been fueled by the verbiage contained in this instruction which, when isolated from its content, seemingly authorizes the jury to monitor our level of accuracy and to question our judgment when interpreting at the witness stand. Those concerned contend that allowing jurors to challenge our skills based on a juror’s “belief” could undermine the value of our qualifications and our official role in the judicial process, arguments that deserve adequate discussion. However, prior to determining their merits, the substance of the instruction rather than the form must be analyzed. Only then will we be able to determine either if we are being monitored or if the instruction attempts to preserve the integrity of the jury.

Initially, it should be noted that this instruction concerns jurors who “understand” the language spoken by the witness and are capable of “retranslating” the English interpretation of testimony given in a foreign language to other jurors. It addresses only those jurors who, based on their knowledge of a foreign language, may tend to disagree with the official interpretation of testimony, and possibly reject it in favor of their own version.

When such bilingual jurors are present in a jury pool, concerns over their ability to set aside their own understanding of what a non-English speaker has testified to in favor of the official English interpretation are usually addressed in voir dire by asking for a promise to adhere to the English rendition of testimony provided by the court interpreter. A juror who was reluctant to promise could be challenged for cause. Notwithstanding the promises made during voir dire, however, implicit misgivings remain as to whether bilingual jurors can voluntarily disregard what they believe to be interpreting errors and not consider them in their own deliberations.

Bilingual jurors do not operate on a level playing ¬field with jurors who speak only English because they have the ability to hear a witness’s testimony twice.

Fundamental tenets of justice underscore the purpose of this instruction. First, fairness requires that all jurors consider the same evidence, and each side must be assured that the evidence they have presented is in fact the evidence that is being considered by all the jurors. CALCRIM Instruction No.101 cautions the jury: “It is unfair to the parties if you receive additional information from any other source because that information may be unreliable or irrelevant. Your verdict must be based only on the evidence presented during trial in this court….” [CALCRIM No.101, Cautionary Admonitions: Jury Conduct (Before, or After Jury is Selected) (2013)] This mandate requires all jurors to consider the officially interpreted sworn testimony as the only evidence received from that witness.

Second, the record of the proceedings is preserved only in the English language, and it is this recorded testimony that constitutes the official record of the verbal evidence in the case. As testimony given in a language other than English is not recorded, and only the official interpretation is evidence, allowing a bilingual juror to introduce his or her own unofficial, inadmissible interpretation during deliberations for other members of the jury can taint the integrity of the record, as well as prejudice the jury.

Bilingual jurors do not operate on a level playing -field with jurors who speak only English because they have the ability to hear a witness’s testimony twice. While the English-speaking jurors wait for the English interpretation of the witness’s testimony, the bilingual juror has the ability to appreciate and reflect on nuances of language not readily understood by the English speaker. After hearing both renditions, the bilingual juror has the opportunity to decide which version to accept or reject, notwithstanding the rule that the actual oral response cannot be regarded as evidence.

CALCRIM No.121 attempts to repress the natural tendency of bilingual jurors to interpret for themselves original answers given by a witness in a language they understand. It affirms the juror’s duty to “rely on the translation provided by the interpreter.” The juror must trust, depend on, and place full confidence¬ in the official interpretation, and treat the witness’s testimony as if the witness had spoken English with no interpreter present.

CALCRIM No.121 is based on People v. Cabrera, 230 Cal. App. 3d 300, 303-04 (1991). In that case, the defendant was convicted of committing lewd acts upon his stepdaughter. (Id. at 302). After his conviction, defense counsel learned that a juror had expressed disagreement during deliberations with the English interpretation of defendant’s testimony given in Spanish. The juror informed other jurors that defendant testified he had “pushed” his stepdaughter when attempting to get her to do her chores, rather than “touched” her, as his testimony had been interpreted. (Id. at 302). Defendant brought a challenge based on alleged jury’s misconduct in a motion seeking a new trial. The motion was denied, and the defendant appealed. (Id. at p.303)..

On appeal, the defendant did not raise the issue of the accuracy of the interpretation. Instead, the defendant objected to the juror’s conduct during deliberations, framing this issue as follows: “Did a juror commit misconduct in [reinterpreting] for other jurors a portion of testimony as [interpreted] by the court interpreter?” (Id. at p 304)

The court held that the juror “committed misconduct by failing to rely on the court interpreter’s [interpretation] as she promised she would during voir dire.” (Id. at p.305.) It also held that “the juror committed further misconduct by sharing her personal translation with her fellow jurors, thus introducing outside evidence into their deliberations.” (Id. At 305.) In its ruling, the court stated: “If [the juror] believed the court interpreter was [interpreting] incorrectly, the proper course of action would have been to call the matter to the trial court’s attention, not take it upon herself to provide her fellow jurors with the “correct” [interpretation].” (Id. at p.305.)

CALCRIM No.121 adopts the language of Cabrera almost verbatim, telling the jurors on behalf of the judge: “If you believe the court interpreter translated testimony incorrectly, let me know immediately by writing a note and giving it to the (clerk/bailiff).”

The intended function of the instruction is to discover any disagreements a juror may have with the interpretation so that any dispute can be resolved by the court prior to deliberations. As written, however, the instruction may lead bilingual jurors to conclude that they are expected to determine if the court interpreter has rendered an accurate interpretation of the testimony. This conclusion presents the opportunity for jurors to launch unnecessary challenges against the court experts in language at the risk of minimizing their responsibility to rely on the official interpretation.

If this practice were to become common, other dangers could be anticipated. Confidence in the reliability of the court interpreter’s role to provide equal access to justice for those who are unable to communicate in the English language could be undermined. Because litigants and witnesses depend on the interpreter to understand what is being said, a relationship of trust is created that should be protected at all costs. It is necessary for others as well to feel confident that they can rely on the accuracy and expertise of the interpreter. For example, in order for defendants to effectively assist their attorneys in their own defense, they must trust that the interpretation of the proceedings is accurate and complete.

If the juror’s note is not handled properly, the attention could focus on the interpreter’s performance rather than addressing a juror’s disagreement. A natural inquiry would be: has the interpreter affected the testimony by committing an error or mistake? The parties could also raise concerns about the competency, levels of accuracy, and qualifications possessed by the interpreter, using these issues as the basis to challenge the testimony or the interpretation of it.

Although these questions may ultimately be the subject of judicial inquiry, they are not appropriately raised by the juror’s note. After receiving a Cabrera note, the court should only consider any alleged discrepancies or inaccuracies in the interpretation that was provided in court. Once that determination is made, the parties should have the assurance that the jurors will base their decision solely upon the interpretation accepted by the court, even if a question remains in a bilingual juror’s mind as to its accuracy.

[Joel Rubert, J.D., is a certified court interpreter at the Orange County Superior Court. He can be reached at jerubertjd@gmail.com.]

What’s Going on in Immigration Courts?

By Dan DeCoursey

A new language service provider offering lower rates. Some interpreters refusing to sign the contract. Fiery blogs alleging unfair treatment. No, I’m not talking about court interpreters in the United Kingdom. I’m referring to what’s going on in immigration courts here in the United States.

My intention in this article is not to take sides, but rather to look more closely at the immigration courts to understand how we got here, and where we could go from here.

Like many NAJIT members, I am a court interpreter who has never worked in immigration courts. Nonetheless, I consider immigration court interpreters my colleagues, and I believe it’s important to keep abreast of their working conditions. Delving into this situation, however, has not been easy. I was very disappointed to find that Google searches were turning up virtually no articles on the situation, not even from local news sources. Moreover, labor disputes are contentious affairs, and this one is no exception. Emotions can run high, and objective viewpoints can be hard to come by. The fact that many of the interpreters most familiar with this situation are reluctant to speak about it openly makes writing about this topic even more daunting. My intention in this article is not to take sides, but rather to look more closely at the immigration courts to understand how we got here, and where we could go from here. It is in everyone’s interest that this dispute be resolved as quickly as possible so that our immigration courts may carry out the difficult and essential task of adjudicating removal proceedings both efficiently and fairly. Perhaps a little background information could help.

Immigration Courts Are Not Criminal Courts

What surprised me the most in my research is how different immigration courts are from criminal courts. The Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR), an agency within the Department of Justice (DOJ), is charged with adjudicating immigration cases to determine whether certain individuals should be removed from the United States. While criminal courts are part of the judiciary, immigration courts fall within the executive branch of government. These proceedings are considered administrative rather than criminal proceedings. While defendants in criminal court have the option of a jury trial, respondents in immigration court face a bench trial conducted by a sole immigration judge (IJ). In criminal courts, the prosecutor has the burden of proof, whereas in immigration court, the assistant chief counsel only needs to prove alienage, which is often conceded by the respondent. Once alienage is established, then the burden shifts to respondents, who must demonstrate that they qualify for relief from deportation. Unlike in criminal courts, indigent respondents do not have the right to a court-appointed attorney. Those who cannot afford private legal representation and are unable to find a non-profit organization to represent them have no choice but to represent themselves.

In criminal court, defendants with limited English proficiency (LEPs) have a right to be linguistically present during all phases of the proceedings. That is, they have a right to have the entire proceedings interpreted into their primary language. In addition, they are entitled to be physically present during proceedings. In immigration court, however, attorneys may waive their clients’ right to full and complete interpretation of the entire proceedings, in which case only the respondent’s testimony is interpreted. I was told that attorneys often waive interpretation of the preliminary proceedings in understaffed immigration courts so that interpreters are well rested to interpret the respondent’s testimony, which is the longest phase of the proceeding, and the one in which interpretation accuracy is most crucial. Oftentimes, detained respondents appear via video teleconferencing (VTC) equipment. Respondents may request that experts appear telephonically to reduce the costs of their appearances, which are not covered by the court.

Many criminal courts directly hire both staff and contract interpreters to cover their interpreting needs. While the EOIR directly employs some Spanish-language staff interpreters, for the majority of its interpreting needs, the EOIR outsources to a private language service provider to hire, train and assign contract interpreters for immigration courts. One interpreter I spoke with believes that the EOIR is increasingly relying on contract interpreters to cover its interpreting needs. According to one article I found, there are currently 67 staff interpreters and 1,650 freelance interpreters working in immigration courts. (However, it should be noted that some of these freelance interpreters are for rare languages that might only be needed a few times a year.) Not surprisingly, immigration courts rely heavily on interpreters. In 2014, only 15% of individual hearings in immigration court were conducted in English.

A System Overwhelmed

Anyone who works for criminal courts would agree that the past few years have been a rough patch. In most parts of the country, both state and federal courts have suffered hiring freezes, work furloughs, attrition and layoffs. The more I read about immigration courts, however, the more I get the sense that they have been truly overwhelmed. A Google search of “immigration court backlog” will give you an idea. Immigration courts recently broke a record: currently they have a backlog of over a half a million cases. In his testimony to Congress last year, EOIR director Juan P. Osuna said the courts were facing “unprecedented pressure,” in large part due to increased enforcement along the border and the surge in unaccompanied minors arriving from violence-plagued areas in Central America. The Department of Justice initiated “rocket dockets” to quickly resolve the cases of unaccompanied minors. Meanwhile, the average wait for non-priority cases was pushed back nearly two years. Immigration judges’ caseloads increased from an average of 641 cases per judge in 1998 to 1,545 cases in 2014. According to one study, immigration judges have a higher burnout rate than hospital workers and prison wardens. In order to alleviate the backlog, Congress approved additional funding last year to enable the EOIR to hire more immigration judges.

A New Contract

In 2015, Lionbridge’s long stint as provider of contract interpreters for immigration courts ended; the Department of Justice changed gears and awarded the contract to SOS International (SOSi). Lionbridge had been awarded $14 million annually to provide these services, and in the second quarter of last year the company failed to make a profit. SOSi was awarded $12 million to take over the contract in November 2015. SOSi offered interpreters less generous rates, lower travel reimbursements and more limited cancellation policies than those offered by Lionbridge, and according to one source, up to a third of immigration court interpreters refused to sign the contract.

In September of 2015, NAJIT formed an Ad Hoc Immigration Committee. Shortly afterwards, during the meeting of the Translation and Interpreting Summit at the American Translators Association (ATA) Conference in November, the ATA was asked to draft a letter to the EOIR on behalf of several organizations, including NAJIT. The letter expressed the following:

To our understanding, the payment rates and working conditions for interpreters proposed under the new contract let by EOIR pose a significant threat to the orderly operations of the nation’s immigration courts, and therefore to the civil rights of immigrants under EO 12166 appearing in these courts.

We are very concerned that vulnerable minorities will be underserved by unqualified and unprofessional interpreters as a result of the conditions in the contract let by the EOIR.

In addition, it was pointed out that the “rates offered under the new contract undercut the current market significantly,” and that with “additional overheads for recruiting, project management, and quality assurance,” the current contract pricing was “unrealistic.” NAJIT sent its own letter to the EOIR, indicating that “the proposed contract does not require previous work experience for spoken language interpreters and translators nor does it require that spoken language interpreters and translators hold certification.” NAJIT warned of the possibility that qualified interpreters and translators would refuse to provide their services, and the “result will be a considerable and dangerous drop-off in the quality of languages services provided to a very vulnerable population.”

These efforts have appeared to pay off. In certain areas of the country, I was told by several colleagues that interpreters were able to reach a more favorable agreement with SOSi, but this agreement was short-lived. Once it was about to expire towards the end of the preceding fiscal year, SOSi encouraged many contract interpreters to offer more competitive rates. Interpreters I spoke with told me that in certain parts of the country where a large number of contractors refused to lower their rates, SOSi has been hiring out-of-towners to cover the immigration courts’ interpreting needs.

Where Do We Go From Here?

Carmen Febres-Cordero, chair of NAJIT’s Ad Hoc Immigration Committee, told me that many experienced contract interpreters are seeking better opportunities with criminal and civil courts and in medical settings. Those who work exclusively for immigration courts, however, are feeling the squeeze, and for many of these interpreters, negotiations with SOSi appear to have reached a standstill. Febres-Cordero said that the committee is in the process of “gathering information so we can contact the corresponding authorities with facts, in a clear and concise manner.” She is hopeful that the Department of Justice is listening and will analyze the situation to promote any necessary changes.

I hope Febres-Cordero is right. A workable solution agreeable to all parties would allow our immigration courts to avoid what occurred in the courts in the United Kingdom, where thousands of cases were postponed due to a lack of interpreters, many court interpreters moved on to better-paid work and the language service provider eventually declined to bid for a renewal of its contract. With a record backlog of limited-English-proficient respondents, our immigration courts need more than ever a reliable source of experienced interpreters in an enormous variety of languages to function properly and efficiently. For the sake of everyone involved, let’s hope NAJIT’s efforts pay off once again.

[Dan DeCoursey is the editor-in-chief of Proteus.]

NAJIT News

Message From the Chair-up: Winter 2016/17

By Esther Navarro-Hall

What has NAJIT been up to lately?

My dear colleagues,

By now, most of you, if not all, have already visited our stunning new website. Its simplicity and functionality have placed NAJIT squarely in the 21st century as far as websites for professional associations go. Your board and administrators have stayed busy for months with the planning, designing and execution of this venture. We strongly believe NAJIT’s new logo and website add to our efforts to create a fresh look and a modern hub of information, discussion, and innovation for interpreting and translation.

Needless to say, this is the largest project we have undertaken this year. As proud as we are of this step in our association’s growth, however, there is much more going on that we’d like to share with you.

Our association has made great strides lately in committee work. During last May’s conference, we received such compelling offers to volunteer that we have barely been able to keep up with all the ideas, meetings and planning, specifically for some of the issues which you have told us are important to you. For example:

- We have discussed the plight of immigration interpreters and the challenges of indigenous language interpreting with various government entities, and our Immigration Interpreting and Indigenous Language Ad Hoc Committees are staying abreast of the latest developments and creating additional support documents.

- Our Advocacy Committee is currently working on a new initiative which will provide webinar training for colleagues interested in meeting with congressional staff the day before our 2017 conference begins (stand by for more information on “NAJIT’s Lobbying Day” in Washington, DC).

- Our Membership Committee has been hard at work striving to improve the value proposition of NAJIT membership, as well as re-designing some of our recruitment tools to reflect our new and improved look.

- Our Bench and Bar Committee is planning a session at our annual conference to train interpreters on how to present our bench and bar PowerPoint slides.

- We continue to support other organizations’ initiatives, such as Red T’s Open Letter Project. We are proud to say that NAJIT has now become a permanent signatory on this project.

- We are currently drafting a letter in support of the complaint filed by the Spanish Professional Association of Court and Sworn Interpreters and Translators (APTIJ) before the Spanish Ombudsman. APTIJ is currently seeking an investigation of the problems concerning the provision of interpreting services in Spanish courts and police stations, and NAJIT will be adding its voice to this petition.

Communication with our members and interpreters and translators at large is essential for efficiency and creativity in our association and within our profession. To this purpose:

- We have brought back NAJIT’s much-awaited listserv. If you have not had a chance to say hello to your colleagues or initiate a discussion about terminology or professional issues, among many other topics, we encourage you to do so as soon as you get a chance

- Our blog, The NAJIT Observer, is going strong with some amazing recent posts about skills development, challenging interpreting situations, and our popular “What Would You Have Done?” section.

- Our much-loved Proteus has a new online look and some impressive content.

- NAJIT’s e-mail announcements are now reaching thousands of colleagues around the world.

- Our new Job Board on NAJIT’s website is allowing clients and practitioners to post and view job offers from many sources.

In keeping with our enormously successful conference this year, preparation for our 2017 conference is in full swing. Some of the items you can look forward to:

- An outstanding key note speaker to inspire and motivate us all.

- A special day for advocacy activities in Washington, DC, on May 18th, for those of you who’d like to take full advantage of your stay in the area.

- A day packed with pre-conference training sessions, on May 19th, with new and engaging topics.

- A bus tour organized by our Conference Committee, NAJIT Administrators and one of our very own colleagues, to highlight history, the law, and court interpreting in the DC area.

- Authorization from many states to cover your CEU needs.

- A special invitation for attorneys, with possible authorization of CLE units.

- Our excellent presentations and panels, plus fun networking events.

- A lively exhibitors’ hall with books, technology, vendors and prospective employers.

- An incredible deal for one of the premier interpreting/translation conferences in the U.S. Our Call for Exhibitors and Sponsors is now open, and you can already make your reservations for our conference venue. At the $119/night rate negotiated by our terrific administrators, this is one of the best prices you’ll ever get for conference lodging in the DC area. Do not delay. Make your reservations soon!

A couple of additional items I’d like to share with you:

NAJIT’s 501(c)(3), the Society for the Study of Translation and Interpretation (SSTI) is taking on exciting and innovative projects. By the time this issue of Proteus is published, they will have revealed a remarkable first in scholarly research for the legal interpretation and translation community. I am sure you will agree that this is a worthwhile undertaking. Stay tuned for their next project!

Also, in keeping with one of NAJIT’s goals for this term, to become a stronger presence in the international community, I presented at the “X Simposio sobre la traducción, la terminología y la interpretación Cuba-Québec” at Varadero, Cuba on December 6-8. The title of my presentation is “Court Interpreting in the U.S. and the Role of Professional Associations.” Our participation in this symposium is sure to place NAJIT at the forefront of the nascent court interpreting and translation specialty in this beautiful country.

Empowering interpreters and translators is a personal passion of mine. We are thankful that, through the support of our incredible association and our fearless colleagues, NAJIT has embarked on this journey for the past few years. As your Chair, I will keep working hard to move us in that direction. Thus we are thrilled to provide our cherished members with some of the tools needed for this empowerment, and we are busy creating more. We hope you will join us in this journey and help us to continue making the world aware of the great need for our profession and for that language magic we do so well.

I hope you had a great holiday season and I am wishing you all the best in the new year.

In kindness and gratefulness,

Esther

Chair, NAJIT

NAJIT’s Call for Sponsors and Exhibitors for the 38th Annual Educational Conference May 19th – 21st, 2017 is now open

NAJIT welcomes members and friends to its 38th Annual Conference event at the Hilton McLean Tysons Corner located in McLean, VA (the greater Washington, DC area). Don’t miss this unique opportunity to highlight your organization to an influential community of interpreters and translators. The National Association of Judiciary Interpreters & Translators (NAJIT) is dedicated to the mission of promoting quality services in the field of interpreting and translating. Our annual conference is attended by more than 250 members of the growing community of interpreters and translators. With our multiple sponsorship and exhibitor opportunities, we would like to invite you to connect with this community and make meaningful contact with our members. Click here for more information.

Registration is now open for NAJIT’s 38th Annual Educational Conference

NAJIT welcomes members and friends to its 38th Annual Conference event at the Hilton McLean Tysons Corner located in McLean, VA (the greater Washington, DC area). Don’t miss this unique opportunity to highlight your organization to an influential community of interpreters and translators. The National Association of Judiciary Interpreters & Translators (NAJIT) is dedicated to the mission of promoting quality services in the field of interpreting and translating. Our annual conference is attended by more than 250 members of the growing community of interpreters and translators. With our multiple sponsorship and exhibitor opportunities, we would like to invite you to connect with this community and make meaningful contact with our members. Click here for more information.

Regular Columns

How I Handled It

By Marie Ontiveros

I had a case where a man was accused of indecent liberties with a six-year-old girl who was his neighbor. The allegations were disturbing, and the case affected my personal emotions, but I had to remain impartial and interpret for the attorney and his client.

The client decided not to go to trial, but rather to take a plea in exchange for less time in prison. The attorney talked to his client in lock-up to go over the plea agreement, but before he would accept it, the defendant requested to speak with his wife, who was terminally ill. He had the impression that he was never going to see her again, because he was going to prison for three to four years. The defendant said that he wanted to tell his wife that he was innocent.

He had the impression that he was never going to see her again, because he was going to prison for three to four years.

They brought his wife into the room. As soon as the defendant saw his wife, he told her: “I love you with all my heart. I’m innocent. You know that I would never do something like this. We’ve been together for twenty years, and you know I would never do anything like this.”

The defendant’s wife was then escorted out and we came back into the room. As soon as she left the room, the defendant changed from talking as an innocent man, and started talking like a predator..

Among other things, he asked his attorney if he would be able to go back to Mexico after the case was concluded. This was when the conversation took an unexpected turn. Incredibly, the attorney said to the defendant: “You can go to Acapulco and get another girl. What age do you want?”

The defendant laughed and said, “I want to get a little older girl, maybe 8 or 9.”

As I continued to interpret back and forth, both the attorney and client where laughing, talking like adult men might talk about a woman of legal age.

They both looked at me, as if they wanted to see if I was amused as they were laughing. I averted my eyes to avoid having eye contact with either of them. As a professional, I remained composed, but the mother in me was disgusted.

After I finished interpreting for the attorney and his client, I left the courtroom. I usually leave the courtroom by the door in the back of the courtroom, but for some reason that day, I exited through the doors at the front of the courtroom. The defendant’s wife walked behind me and approached me.

“He’s not innocent, right?” she asked.

“I’m sorry,” I told her. “I am the interpreter and I cannot divulge a private conversation between an attorney and his client.” I then walked away and I heard her say, “I know he’s guilty, I’m not stupid!”.

This situation posed a challenge for me. I had to react quickly and not let my anger out that I felt as a mother, listening to grown men talking about abusing children.

I had to maintain a straight face, and be impartial and ethical, especially at the moment that the wife approached me. I could have told her the truth about the conversation, but in so doing I would have violated the interpreters’ code of ethics. Had these men continued to speak in this manner much longer, I believe I would have recused myself from continuing to interpret. In twenty years as a professional interpreter, I have only recused myself twice, but this case was so twisted, I almost felt I could not finish it. Thankfully, I was able to do so.

[Marie Ontiveros has been an interpreter for over twenty years and holds certificates in both medical and legal interpretation from the Southern California School of Interpretation. She is currently a staff interpreter for the state of North Carolina.]

For Better or Verse

Douglas Hal Sillers

The Slimming Scheme

We Interpreters sit. That could cause harm.

We need to stay fit. Exercise is the charm.

Half a mile walk, or short climb up the stair

Keeps a backside from filling all of the chair

Give up some sugar. Cut back on the bread.

Cut down on butter and that other spread.

We don’t need a soda nor bowl of ice cream.

Eat oatmeal ‘n yogurt in a slimming scheme.

Don’t heap second helpings upon your plate,

And as for dessert, well, that surely can wait.

Since Coffee ’n cookies may be our downfall,

We should never succumb to their siren call.

We ought not eat cake, don’t need apple pie,

And for goodness’ sake, let’s not tell a fat lie.

Weigh in every day and drop maybe a pound.

Continue in motion, the weight will go down.

So what is the goal? Do we want to be svelte?

No. Just not to buy Xtra Lrg and a longer belt.

Douglas Hal Sillers 09-09-16

FAQ

Frequently Asked Questions: Printing Proteus

Q: Can I Print Proteus using my computer printer?

A: Yes, all Proteus articles are specifically formatted to print out in readable format on your computer. The print out will not include banner advertisements or comments. You may print individual articles or you can print the entire issue.

Q: Why am I not seeing graphic elements when I print out Proteus?

A: Many webbrowsers come with default settings that do not allow graphics to print. You can easily override these settings so that Proteus graphics print correctly. Below you will find instructions on how to set your browser so that the proteus masthead appears on the printed version of the newsletter.

Internet Explorer

On the Tools menu, click Internet Options. Click the Advanced tab. Under Settings, scroll down until you find the Printing category. Make sure Print background colors and images is checked, and then click OK. You can get more information about this setting at: http://support.microsoft.com/kb/296326

Firefox

On the File menu, click Page Setup. On the Format & Options tab, under Options, select Print background (colors & images). Click OK.

Safari (probably set correctly by default but you might want to check)

On the File menu, click Print. On the Copies & Pages pop-up menu, click Safari. Select Print Backgrounds. Click OK.

Netscape®

On the File menu, click Page Setup. On the Format & Options tab, under Options, select Print background (colors & images). Click OK.

Q: When I print an article some of the content is cut off at the bottom or top of the page.

A: Because your computer is unique, it’s impossible for NAJIT to format Proteus so that it will automatically print correctly on every computer and printer set up. So you may need to preview the print page before you print, so you can adjust your top and bottom margins. From your browser, select Print/Preview. In the preview screen your browser should give you many options, such as shrinking or expanding the text, adjusting margins and other formatting that will allow you to print Proteus from your particular computer setup.

Q: Do I need permission to reprint Proteus articles.

A: If you are planning to print and distribution more than 10 copies of a Proteus article, you should contact NAJIT for specific permission. Any Proteus article that is quoted in other work should be properly credited.