06 May Compensation Policies Show State Court Interpreters are Underpaid

By Sandro Tomasi

Interpreters have long been underappreciated and undervalued in the United States, a situation due mainly to the lack of proper identification of the level of knowledge, skill and ability needed to perform as a competent interpreter. Many people, especially monolinguals, still believe that all interpreting consists of is repeating something word-for-word in another language, which is contrary to accepted practice in the field of interpreting. In addition, there exists a callous sentiment that some people have towards immigrants in this country. Whereas women and African Americans have movements to help their cause (MeToo, Black Lives Matter), immigrants do not have such a clear path for equality. Nonetheless, recent advancements have been made in California and New York, as can be seen by comparing the court compensation policies between interpreters and other job titles. This data shines a light on how state courts have been undervaluing and underpaying for the job of court interpreting.

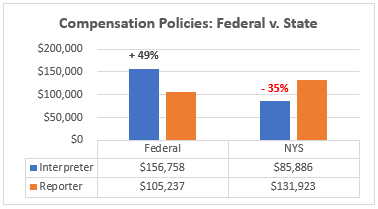

Compensation Policies: Federal v. State

In 2017, the California Federation of Interpreters (CFI) made a crucial compensation comparison of similar job titles between state and federal courts. The comparison revealed that many job titles in the California state courts had salary parity with their counterparts in the federal courts, but that the court interpreter job title had a salary that was about half that of its federal counterpart.

The California Judicial Council uses a different compensation policy for court interpreters.

In 2019, New York State staff interpreters applied the CFI approach and found a similar disparity, i.e., the New York State Unified Court System was also applying a different compensation policy for interpreters than it was for other state employees who were enjoying salary parity with their federal-court counterparts.

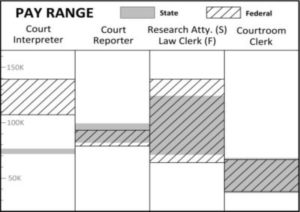

Compensation Policies: Court Interpreter v. Court Reporter

The NYS staff interpreters applied an additional compensation analysis that exposed another massive salary disparity for court interpreters. The analysis was rooted in the fact that court interpreters perform a similar job to court reporters who have to simultaneously translate from English into stenography, yet interpreters receive around 35% less than their coworkers for their simultaneous interpretation of English into another language. Moreover, even though the jobs are similar, interpreting is more difficult than court reporting for a number of reasons. In addition to the fact that it takes longer to learn a language based on culture as opposed to a language based on phonetics (stenography), interpreters also use a culture-bound translation system which is harder to learn and execute than the phonetic-bound translation system used by court reporters. A report published in 2019, entitled Compensation of Court Interpreters in the State of New York (which may be the first empirical work that goes into an in-depth, comparative analysis of the knowledge, skills and abilities of court interpreters and reporters), demonstrates these assertions based on empirical data.

The federal courts have recognized that the court interpreter job is more demanding than that of a court reporter by compensating interpreters about 49% more than court reporters. This compensation policy stems from the 2008 Judicial Conference (the national policy-making body for the federal courts), which adopted a new “landmark standard” setting grade JSP-14 for federal staff court interpreter positions, noting that staff court interpreter positions are highly specialized.1

The New York State Unified Court System uses a different compensation policy for court interpreters.

The question is which of the charted court compensation policies is correct: federal or state? The answer is clear when taking into consideration the job classifications of interpreters and court reporters by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. The EEOC classifies interpreters and translators as “professionals”—just like judges, doctors and lawyers—and court reporters as “administrative support workers.”2 Moreover, the findings of the aforementioned 2019 compensation report also corroborate the federal court compensation policies for interpreters and reporters.

Comparative Qualifications and Compensations of Court Employees

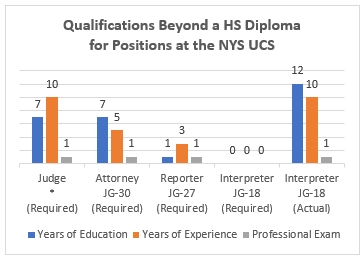

Knowledge, skills and abilities (KSAs) are objective measures used to help employers determine whether a person has the theoretical understanding and the skills to show that they have put their knowledge to use for a particular job. Employers also look to qualifications, such as passing a professional exam, as proof of a skill or skills. Human resources decide the KSAs needed for various job titles and establish how much education and experience is needed to perform each particular job in order to allocate the appropriate compensation.

The New York State Unified Court System (NYS UCS) requires judges to have 7 years of education beyond high school, 10 years of experience practicing law and to pass a bar exam. New York State judges receive a maximum salary of $208,000 a year. The highest level of court attorney in the NYS UCS has the same requirements, except for that of experience, which is set at 5 years, and is compensated at a maximum salary of $151,766 a year. The highest level of non-supervisory court reporter is required to have a high-school diploma and one year of stenographic studies, plus three years of experience, and is compensated with a maximum salary of $131,923 a year. The NYS court interpreter job title only requires a high-school diploma and is allocated a maximum salary of $85,886 a year.

The New York State Unified Court System’s compensation policy for court interpreters is based on undervalued qualifications.

If the federal courts, by way of the Judicial Conference, have set compensation policies for court interpreters to be paid at higher rates than court reporters, and the EEOC’s job classifications corroborate this policy, state courts around the country will have to reevaluate their assessment of the KSA’s, education and experience needed for competent court interpreters.

The salaries in the previous paragraph roughly correlate with the required qualifications, education and experience for each job title (chart below). However, according to the aforementioned 2019 compensation report, the NYS UCS has undervalued the numbers pertaining to an interpreter’s education, experience and qualifications by only requiring a high school diploma. Neither having native-like fluency in a second language nor higher education are required as qualifications. According to second language acquisition experts, it takes an 8-year average of second language immersion, not just language classes, to reach native-like fluency.3 In 2018, a survey by the Court Interpreter Chapter of Local 1070/AFSCME DC-37 demonstrated that most staff interpreters have a bachelor’s degree or higher, which correlates with industry standards.4 Furthermore, a survey of NYS staff interpreters conducted in 2019 evidenced that they have an average of 10 years of work experience at the time of hiring.5 When the education numbers (8+4 yrs.) and experience numbers (10 yrs.) are calculated in along with the fact that interpreters have to pass a professional exam (which is not currently required in the NYS court interpreter job title), the numbers reveal that an interpreter’s actual qualifications are higher than the ones required for judges by the NYS UCS.

If the federal courts, by way of the Judicial Conference, have set compensation policies for court interpreters to be paid at higher rates than court reporters, and the EEOC’s job classifications corroborate this policy, state courts around the country will have to reevaluate their assessment of the KSA’s, education and experience needed for competent court interpreters. Interpreting is still a relatively young profession in this country and there is a lot of room for improvement, including setting the appropriate compensation policies for interpreters, who just may be the most skilled persons in a courtroom.

References:

[1] Judicial Conference of the United States (September 16, 2008, Washington D.C.; June 17, 2008, Special Session). Report of the Proceedings of the Judicial Conference of the United States, 26. United States Courts. https://uscourts.gov/sites/default/files/2008-09.pdf

[2] EEO-1 Job Classification Guide 2010. (n.d.). U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Retrieved on February 25, 2020 from https://eeoc.gov/employers/eeo1survey/jobclassguide.cfm

[3] Hill, Jane D. & Cynthia L. Björk (September, 2008). Classroom Instruction That Works with English Language Learners Facilitator’s Guide. ASCD. http://ascd.org/publications/books/108052/chapters/The-Stages-of-Second-Language-Acquisition.aspx

[4] Court Interpreter Chapter, Local 1070/AFSCME DC 37 (February, 2018). Interpreter Survey (N=70).

ATA Interpreters Division (May, 2015). ATA Interpreters Division Report to ATA Board of Directors: May 2015 Survey Results, Conclusions and Recommendations (N=536). http://ata-divisions.org/ID/wp-content/uploads/reports/Survey-ATA-ID-May-2015-Report-Board-Graphics-10222015.pdf

Kelly, N., Stewart, R. G., & Hegde, V. (June, 2010). The Interpreting Marketplace: A Study of Interpreting in North America (N=1,140). InterpretAmerica, Common Sense Advisory. https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/c931a5_5a9d21e556c74858a940b18821b8db09.pdf

[5] Tomasi, Sandro (September, 2019). NYS Staff Court Interpreter Survey (N=56).

[Sandro Tomasi has been a Spanish-English interpreter and translator since 1991. He is a New York State staff court interpreter and a certified medical interpreter by the State of Washington. Sandro is the author of the authoritive and acclaimed lexicographic work, An English-Spanish Dictionary of Criminal Law and Procedure (aka Tomasi’s Law Dictionary), and a contributing author of Black’s Law Dictionary, 11th ed. and Cabanellas de las Cuevas and Hoague’s Diccionario Jurídico, Law Dictionary, 2nd ed. Sandro has served as chair of NAJIT’s Education Committee and currently serves as chair of the Advocacy Committee.]

The views and opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official position of NAJIT.

Good day, I have been a licensed Judiciary Interpreter since 1987. As such, I have translated and interpreted for many federal and state agencies from Florida to California and have sometimes worked as a subcontractor for large “language” companies as part of their “team” of “professional interpreters in helping federal and state agencies communicate with LEP’s. Most of the times, it turns out that I am pretty much the only actually trained and licensed interpreter of the group!

With this being the case in most states to include the Southern border ones, New York and others, I am conviced that that the undervaluation and underappreciation of licensed (whether court, medical, state or federal) translators and interpreters is largely a result of so many, the most actually, large “language” companies taking advantage of their size, business and political connections and the laxity of the laws, to pretty much monopolize the market, and who, as a normal practice, hire unlicensed “interpreters” just because they happen to be “bilingual”, to render translations and interpreterships yet turn around and sell their services as “highly qualified”. The underqualification, of course, gives these companies the best justification to underpay their “professionals” and undermines the true translators and interpreters thanks to the myriad of mistakes and misrepresentations made in both written and oral presentations. I have noted that this phenomenon has spilled into goverment and judiciary service as well. It is my belief that, until such a time in which federal and state law really makes it impossible for unlicensed, untrained and untried translators and interpreters to “practice” (as in the case of court and, in many states, medical services) in ANY respect, along with ongoing efforts to educate our customers is that we, as licensed professionals, will not see any improvement in the appreciation and, specially, valuation of our work.